Archive

Cultural Politics – a new MA course at WSA

A new MA course at the Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton is now validated and online. The course, jointly run with Politics department, will run starting in 2017. You can find more information about the course here. The journal Cultural Politics (Duke University Press) is already now partly run from WSA (with John Armitage and Ryan Bishop as editors) and this MA course can nicely consolidate some of our research interests in media, art/design and politics in the form of a new exciting cross-discplinary MA course. If you want more information about the MA, please do get in touch with us.

The Office Experiment: An Interview with Neal White

Here’s a short interview chat we had with Neal White on art practices in and out of the lab, the office and more:

Neal White runs the Office of Experiments, a research platform that “works in the expanded field of contemporary art.” The Office employes methods of fieldworks and works with a range of partners including scientists, academics, activists and enthusiasts, and described as exploring “issues such as time, scale, control, power, cooperation and ownership, highlighting and navigating the spaces between complex bodies, organisations and events that form part of the industrial, military, scientific and technological complex.” Neal White is also starting as Professor at Westminster University, London.

This interview, conducted via email in June and July 2016, was set in the context of the What is a Media Lab-project and aims to address the questions of artistic practice, labs and the (post)studio as an environment of critical investigations of technological and scientific culture. Another,longer, interview with Neal White, conducted by John Beck, is published in the new edited collection Cold War Legacies (Edinburgh University Press, 2016).

JP: Can you start by describing what the Office of Experiments does? I am interested in its institutional form in the sense also Gilles Deleuze talks of institutions as “positive models for action” in contrast to law being a limitation on action. The Office also carries the legacy of modern institutional form par excellence – not the artist’s studio with its romantic connotations, not the laboratory either with its imaginary of science, but the office as an organizational site. Why an office?

NW: The Office of Experiments makes art through a process of collaboration in which all of those who undertake research, make or apply thinking to a project can be credited. We bring together artistic forms of research with experimental and academic research in the field, undertaking observational analysis, archival research, road trips, building platforms and prolonged formal visual studies that reflect the complexity of the subjects we approach. Our approach is to build a counter rational analysis or account of the world in which we live. To move this away from any poetic vision, we draw on ideas from conceptual art, and disciplines such as geography and science studies, architecture and political activism, as well as looking at physical space, data, and the material layer which connects the observatories, global sensors etc of our contemporary world; the interface between the technological and material world.

Having some formative education in Digital Arts, an MA in 1997 and then running a successful art and technology group in Shoreditch, London, in late nineties and up to 2001 (Soda), my experiences collaborating with others was critical to how I work now, and the work of others that interests me. As I wanted to deliberately move away from the hermetic space that media / digital art was creating for itself – the Lab, and to set up an independent contemporary art practice, that moved across spaces, enclosures, archives, in and out of galleries, often working in situ, and which was networked, I needed to find a way of working with others that was neither exploitative nor driven by serving another discipline or field.

Having opened conversations with John Latham in 2002-3, the now late British artist, I was introduced to Artist Placement Group. I was strongly influenced at this point both by Latham’s ideas of time/temporality (as applied to institutions) as well as incidental practices, and I applied those in an instituent form (Raunig) as Office of Experiments. The Office was therefore the solution to working collaboratively as an artist in a critical way, so that credit would be spread, and all those collaborating within each project get something out – whether as art or as an academic output/text, relevant to their individual discipline.

I was attracted to the term Office initially as it holds some idea of power, when thinking of a government department or Bureau, but is also instrumental – something that I felt was and is increasingly asked of art (evaluating audiences for funding etc). However, Office alone does not work, it is too close to that which it is critical of, so it is only when used with the term experiment, and the ideas of experimental systems (Rheinberger), which were also key to my work at this time, that an agonistic dichotomy comes to the fore. This works for me, as we could say the terms are counter-productive, the name undermines itself linguistically (i.e. As Robert Filliou put it “Art is what makes life so much better than Art’). In this respect, it serves the ideas that shape our research, to create a form of counter-enquiry that can hold to account the rational logic of hard scientific enquiry, ideas of progress, the ethical spaces of advanced industry and scienc

The link to post-studio practices and discourse is a thread that runs through the projects. Can you talk a bit more about the other sorts of institutional spaces or experiments in and with regulated spaces such as the laboratory that your work has engaged in?

To give some concrete examples, OoE was founded when working on an experimental platform, which was based on the design of a planetary lander, but we designed it for ‘on earth’ exploration; Space on Earth Station (2006), with N55 (DK). Later, OoE challenged the ethical space of clinical research in a project that used restricted drugs to explore ‘invasive aesthetics; The Void’ in which participants urine is turned blue. Our aim to move the site of the artwork to inside the body. We then explored the history of psychopharmacology and the use of so-called ‘truth serums’ in psychology of torture by the US military. More recently the Overt Research project made visible and navigable the concealed sites, laboratories, infrastructures, networks and logistical spaces of the UK’s knowledge complex, part military, part techno-scientific, a post-industrial complex. In Frankfurt, Germany, OoE acquired a piece of network infrastructure, – a cell phone tower in the shape of a palm tree, whilst we researched quantum financial trading networks and conspiracy theories based around Frankfurt itself. Currently, we are working on data from a globally distributed seismic sensor used to monitor the test ban treaty on nuclear weapons, and have used the data (which is not straightforward to acquire) from this vast instrument to create resonant physical audio experiences around what we call hyper-drones. In many of the cases, projects lead to engagements with society and the public on subjects of concern, whilst also providing tools, resources and shared knowledge with other researchers, enthusiasts and artists.

Considering art history and history of science, the studio and the lab can be seen as two key spaces of experimentation and the experiment, following their own routes but in parallel tracks as well. Does a similar parallel life apply to the post-studio, and the post-lab in contemporary context? In your view, what are the current forms that define the lab?

Starting with any lab today, we could perceive a hyper-structure (Morton) – that is a lab networked to other lab space, and not something discrete or visible as an observable object in the singular. To this extent, labs are also entry points connecting physical and digital layers; they reveal regulatory and permission based cultures in which ethics, health and safety, security and received opinion (Latham)/knowledge assert control. The idea of a lab therefore for art or media art, with any kind of techno-scientific logic not only implies but actually enforces limits (Bioart so often falls down in these terms). Whilst a studio gives an artist working within the constraints of their ability/media a private space to think and work, I find both underline both certain kinds of limits and a tradition of building through a controlled approach to both the experiment and experimentation.

In terms of the post-studio / lab, the ‘social’ (Latour) framing of art in the contemporary field of relations, social engagements and critical practices, experiments are produced through a scale of 1;1, but are also modelled in new ways. So this implies, that we not only need to find a new way to work, but to be present somewhere/somehow else.

So, if Office of Experiments projects explore space and time as dimensions of practice, then it is reflective of these shifts, being made up of a group or number of individuals, we are arguably post-studio in form. Where we might be sited is fluid too, but we do share an enthusiasm for working together by being situated in fieldwork, exploring places and non-sites, as well as complex infrastructures, some which are legally ‘out of bounds’ or ‘off limits’. So we have often worked together to produce platforms for research in the field that include methods as much as architectural projects, as well as resources such as archives and databases, to enable our activities to take place.

Whilst the work we have produced is shown inside leading galleries internationally, as performances, video, visual artwork and installation, we have also produced a number of bus tours, installations, temporary monuments and projects beyond these enclosures, in public space, the landscape or framed by urban and suburban life. So the spaces, or non-sites we work in are also the places in which we exhibit the work, including across media – on the scale of 1:1.

However, the idea of a scale of 1:1 I have wrestled with since reading Rheinbergers work on experimentation, as you could argue that it does not apply to the non-material word we inhabit. Perhaps it is more accurate to say, I have been looking at contemporary forms of production, rather than simply experiments, to think about or challenge these models of working as an artist in a social or collaborative context. For example, what happened in the lab can now be modelled inside the computer, across the network etc. And what was fabricated in the studio for the gallery, can be outsourced and produced by artisans to a better standard, or scanned, modelled and printed, for display across a range of spaces, real or not.

Art has therefore been subject to de-materialisation that started in the 1960’s (see Lippard), but as with so much of late capitalism and scientific and computational processes, it is no longer simply invisible but reduced to the indivisible, distributed and then reassembled. And the site of the reassembling is multiple, as are we.

Earwitnesses of a Coup Night

Update: This text is published inGerman in the Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft‘s blog, translated by Florian Sprenger. It is also published in Turkish in Biamag, translated by Doğan Terzi. Here is the original English version, which is also published on the Theory, Culture & Society journal’s blog.

Earwitnesses of a Coup Night: The Many Media Infrastructures of Social Action

The particularly cruel scenes in Ankara and Istanbul from July 15th and 16th circulated quickly. From eye witness accounts to images detached from their context, media users, viewers and readers was soon seeing the graphic depictions of what had happened with the added gory details, some of them fake, some of them not.

Still and moving images from the hundreds of streams that conveyed a live account of the events left many in Turkey puzzled as to what is going on. Only later most were able to form some sort of a picture of the events with the coherence of a narrative structure. By the morning the live stream on television showed military uniform soldiers raising their hands and climbing down from their tanks. What soon ensued were the by already now iconic images of public punishment: the man with his upper torso bare and the belt as his whip, the stripped soldiers in rows shamed and followed up by the series of images of expressions of collective joy as most of Turkey was relieved again. The coup was over. The unity in resisting the coup was unique. As it was summarised by many commentators: even the ones critical of the governing AK Party’s politics agreed that this was not a suitable manner of overthrowing an elected government.

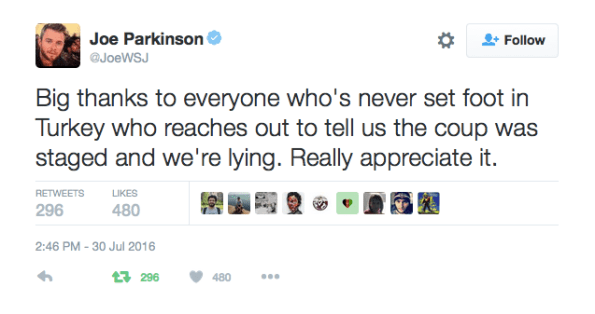

However, what became evident immediately in the wake of the actual events was the quick spread of narratives and explanations about the coup night and its extent. As one journalist aptly and with a healthy dose of sarcasm put it:

The flux of commentaries on social media and in newspapers, columns and television deserved its own name: “coupsplaining” as @shokufeyesib coined it.

Also some rather established organisations like Wikileaks got quickly on the spectacle-seeking bandwagon of the coup attempt’s repercussions. Turkish journalists and activist soon read and revealed that the so-called “AKPleaks”-documents were not really anything that interesting as it was advertised to be. As Zeynep Tufekci summarised: “According to the collective searching capacity of long-term activists and journalists in Turkey, none of the ‘Erdogan emails’ appear to be emails actually from Erdogan or his inner circle” while actually containing information that could be considered harmful to normal Turkish citizens instead.

Of course, besides commentators inside and outside Turkey, there was no lack of people with first-hand experience. Besides the usual questions that eyewitnesses were asked in many news reports about “how did things look like”, another angle was as pertinent. How did it sound? The soundscape of the coup was itself a spectacle catered to many senses: the helicopters hovering around the city; the different calibre gunfire that ranged from heavy fire from helicopters to individual pistol shots; individual explosions; car horns; sirens, and the roaring F-16 that descended at times so low so that its sonic boom broke windows of flats. Such sonic booms have their own grim history as part of the 21st century sonic warfare as cultural theorist Steve Goodman analysed the relation of modern technologies, war and aesthetics. As has been reported for years, for example Israeli military has used sonic noise of military jets in Palestine as a shock technique: “Palestinians liken the sound to an earthquake or huge bomb. They describe the effect as being hit by a wall of air that is painful on the ears, sometimes causing nosebleeds and ‘leaving you shaking inside’.”

In the midst of sonic booms, a different layer of sound was felt through the city: the mosques starting their extraordinary call to prayer and calls to gather on the streets. The latter aspect was itself triggered by multiple mediations that contributed to the mobilization of the masses. Turkish President had managed to Facetime with CNN-Turk’s live broadcast and to call his supporters to go on the streets to oppose the coup attempt. By now even the phone the commentator held has become a celebrity object with apparently even $250,000 offered for it.

But there was more to the call than the ringtone of an individual smartphone. In other words, the chain of media triggers ranged from the corporate digital videotelephony to television broadcasting to the infrastructures of the mosques to people on the streets tweeting, filming, messaging and posting on social media. All of this formed a sort of a feedback-looped sphere of information and speculation, of action and messaging, of rumours and witnessing. Hence, there was more than just traditional broadcast or digital communication that made up the media reality of this particular event.

The mosques started to amplify the political leadership’s social media call by their own acoustic means. Another network than just social media was as essential and it also proved to be irreducible to what some called the “cyberweapon” of online communications. As one commentator tried to argue commenting on the events in Turkey: “But, this is the era of cyberpower. Simply taking over the TV stations is not enough. The Internet is a more powerful means of communication than TV, and it is more resilient — especially with a sophisticated population.” However, there were also other elements in the mix that made it a more interesting and a more complex issue than merely about the “cyber”.

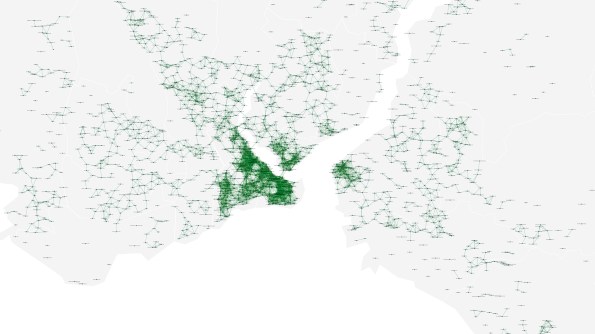

Turkish artist and technologist Burak Arikan had already in his earlier work mapped the urban infrastructure of Istanbul in terms of its mosques, malls and national monuments. “Islam, Republic, Neoliberalism” (2012) employs his critical mapping methodology to visualise how structures of power are part of the everyday whether we always realise these relationships or not. Based on his research, Arikan devised three maps of those architectural forms and how they connect. According to Arikan, the “maps present a comparative display of network patterns that are formed through associations linking those architectural structures that represent the three dominant ideologies –Islam, Republic, Neoliberalism– in Turkey.”

During the coup weekend, it was the network of the mosques and their minarets that became suddenly very visible – or actually, very audible. While the regular praying times have become such an aural infrastructure of the city that one does not necessarily consciously notice it, the extraordinary calls from imams reminded how dense this social, architectural fabric actually is. The thousands of Istanbul mosques became itself an explicit “sonic social network” where the average estimated reach (300 meters) of sound from the minarets is too important of a detail to neglect when one wants to understand architecture as solidifying social networks in contemporary Turkey. In the context of mid-July it was one crucial relay of communication between the private sphere in homes, the streets and the online platforms contributing to the mobilization of the masses. The musicological perspective has highlighted how sound and noise negotiate conflict across private and the public and we can extend this to a wider media ecological perspective too. This is where art and design practices can have an instrumental role to play in helping us to understand such overlapped media and sensorial realities.

Artists such as Arikan have investigated the ways how online tools and digital forms of mapping can connect to issues of urban planning and change. The visual artwork helps us to also understand how there are other social realities, less front of our eyes even if they are in our ears. This expands the wider sense of how media is and was involved in Turkey’s events, and it gives also insights to new methodologies of artistic intervention in understanding the coupling of media, architecture, visual methods and the sonic reality of urban life. And in this case of the bloody events of the coup weekend, much of the personal experience of “what happened” is now being narrated in Turkey in terms of what it sounded like – another aspect of the media reality of the coup attempt’s aftermath.

A Museum of Viruses

I just submitted to the publisher the new, 2nd and revised edition of Digital Contagions: A Media Archaeology of Computer Viruses, a book that came out for the first time with Peter Lang in 2007. Around the time of submission, the new Archive.org online museum of computer viruses was launched and made rounds in the popular press too.

Already in 2002, Museum for Applied Art in Frankfurt am Main, Germany engaged in exhibiting viral art its I Love You-Exhibition. Curator Franziska Nori expressed the importance of this topic: museums and cultural centres need to engage with this new form of cultural activity that tells the story of hackers and programming skills. The museum was to become also a laboratory where new cultural phenomena of digital culture are given a voice.

I wrote a general audience piece about the new Malware museum for The Conversation. For those of you who read German, Die Süddeutsche Zeitung wrote a piece “Unterhaltsame Viren“. The new edition of Digital Contagions should be out by late 2016, or early 2017, just suitably to celebrate its 10th year!

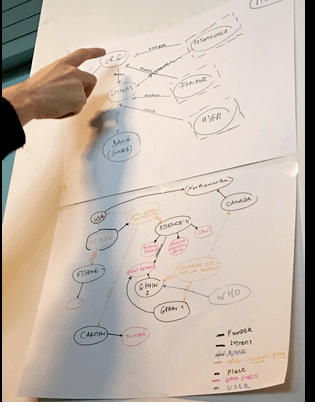

Graph Commons & Critical Mapping

For some years now, Winchester School of Art has been a (university) partner of the transmediale art/digital culture-festival. We took part this year again, with several panels and other events as part of the Conversation Piece-theme.

One of them was the two day-workshop with artist, designer Burak Arikan (tr/new york) who ran a Graph Commons-workshop.

We also had a longer conversation about his work, critical & collaborative mapping and more. You can listen to it as a podcast now.

Media Theory in Transit – a symposium at the Winchester School of Art

Media Theory in Transit: A one-day symposium at the Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton,

November 24, 2015.

organised by Jussi Parikka and Yigit Soncul

Media theory is in transit: the concepts travel across space and time, claiming new meanings for new uses along the way. We are not dealing with a static body of knowledge, but a dynamic, situated process of articulating knowledge and perceiving reality. Media theory crosses both geographical and disciplinary boundaries. It trespasses the border between Humanities and Sciences, and is able to carve out new sites of knowledge. It moves across conceptual lineages from human to non-human, and supposedly distinct senses such as sight, hearing and smell. Media theory is not merely a reflection on the world but an active involvement that participates in creating the objects of interest.

This event investigates such conceptual, geographical and sensorial passages of media theory. The talks address contemporary media theory and issues that are now identified as urgent for academic and artistic practices. The speakers represent different fields of arts and humanities as well as media theory, and engage with the question: how does theory move, and itself occupy new areas of interest, across academic fields and across geographies, in which theory itself is set to be in movement.

The event is supported by the Santander-fund, via University of Southampton and the Faculty Postgraduate Research Funds.

Media Theory in Transit is open and free to attend but please register via Eventbrite!

Schedule

The PhD Study Room (East Building)

10.30 Introduction by Yigit Soncul and Jussi Parikka

10.40 Erick Felinto (State University of Rio de Janeiro, UERJ): “Vilém Flusser’s ‘Philosophical Fiction’: Science, Creativity and the Encounter with Radical Otherness”

11.30 Joanna Zylinska (Goldsmiths, London): “The liberation of the I/eye: nonhuman vision”

12.20 lunch break

14.00 Shintaro Miyazaki: (Critical Media Lab, Basel): “Models As Agents – Designing Epistemic Diffraction By Spinning-Off Media Theory”

14.50 Seth Giddings (WSA): “Distributed imagination: small steps to an ethology of mind and media”

15.20 Jussi Parikka (WSA): “Labs as Sites of Theory/Practice”

15.50 short summary discussion

16.10-16.30 Jane Birkin (WSA) “The Viewing of Las Meninas” (performance)

“Sex, annotation, and verité totale”: Kurenniemi’s Archival Futurism

I am very glad to announce that Writing and Unwriting (Media) Art History: Erkki Kurenniemi in 2048 is out from the printers, hot off the (MIT) Press! Edited with curator, writer Joasia Krysa, the book focuses on the Finnish media art pioneer Kurenniemi, and is the key international collection on the curious thinker, sound and media artist-tinkerer, who became known for his remarkable synthetizers and archival futurism. Kurenniemi has gathered attention in the electronic music circles for a longer period of time, and with Documenta 13 he become known in the international art world too. His thoughts and work resonate with the work of other early pioneers; Simon Reynolds once called him a mix of Karlheinz Stockhausen, Buckminster Fuller, and Steve Jobs. In 2002, Mika Taanila directed the film The Future is Not What It Used to Be about Kurenniemi.

I am very glad to announce that Writing and Unwriting (Media) Art History: Erkki Kurenniemi in 2048 is out from the printers, hot off the (MIT) Press! Edited with curator, writer Joasia Krysa, the book focuses on the Finnish media art pioneer Kurenniemi, and is the key international collection on the curious thinker, sound and media artist-tinkerer, who became known for his remarkable synthetizers and archival futurism. Kurenniemi has gathered attention in the electronic music circles for a longer period of time, and with Documenta 13 he become known in the international art world too. His thoughts and work resonate with the work of other early pioneers; Simon Reynolds once called him a mix of Karlheinz Stockhausen, Buckminster Fuller, and Steve Jobs. In 2002, Mika Taanila directed the film The Future is Not What It Used to Be about Kurenniemi.

The book includes foreword by the eminent media archaeologist Erkki Huhtamo and a range of critical essays on digital culture, archival mania and media arts. Key academic and art writers address Kurenniemi’s work but also more: the condition of the archive and sound arts, sonic fiction and speculative futures of singularity are some of the key themes that run through the book with contributions by many established names in media studies, art and sound technologies. In addition, we included many of Kurenniemi’ own writings over the decades, including some interviews that elaborate his wider computational views of the world, including his thought: by 2040s, the human brain can be completely simulated. His archive plays a key role, like an actor in itself: the archive also featured as a key “object” as part of the earlier Kiasma exhibition and we included some snippets, as well as an extensive visual section.

Writing and Unwriting (Media) Art History sits as part of the Leonardo-book series, edited by Sean Cubitt. The book was started by Krysa through her curatorial work at the 2012 Documenta 13 exhibition. It is thanks to Joasia that I am part of the project and she deserves major praise for her amazing eye for detail, enthusiasm and energy in driving this project, from a major exhibition to a book, and more.

Here’s a preview of the book’s table of contents and Huhtamo’s Foreword.

For review copy requests, or other questions, inquiries about the book, please get in touch! We are hosting some book events in Montreal, Helsinki, Berlin and London over the coming months but more info on those separately.

Writing and Unwriting (Media) Art History: Erkki Kurenniemi in 2048, eds Krysa and Parikka

Over the past forty years, Finnish artist and technology pioneer Erkki Kurenniemi (b. 1941) has been a composer of electronic music, experimental filmmaker, computer animator, roboticist, inventor, and futurologist. Kurenniemi is a hybrid—a scientist-humanist-artist. Relatively unknown outside Nordic countries until his 2012 Documenta 13 exhibition, ”In 2048,” Kurenniemi may at last be achieving international recognition. This book offers an excavation, a critical mapping, and an elaboration of Kurenniemi’s multiplicities.

The contributors describe Kurenniemi’s enthusiastic, and rather obsessive, recording of everyday life and how this archiving was part of his process; his exploratory artistic practice, with productive failure an inherent part of his method; his relationship to scientific and technological developments in media culture; and his work in electronic and digital music, including his development of automated composition systems and his “video-organ,” DIMI-O. A “Visual Archive,” a section of interviews with the artist, and a selection of his original writings (translated and published for the first time) further document Kurenniemi’s achievements. But the book is not just about one artist in his time; it is about emerging media arts, interfaces, and archival fever in creative practices, read through the lens of Kurenniemi.

Endorsements

“Sex, annotation, and verité totale: Kurenniemi is a missing mixing desk between so many interesting aspects of late-twentieth-century culture. No wonder he ends up offering us a new archival futurism!”

—Matthew Fuller, Professor, Director of the Centre for Cultural Studies, Goldsmiths, University of London

“Providing a long-overdue critical and historical introduction to the amazingly multifaceted work of media pioneer, visionary thinker, and self-archivist Erkki Kurenniemi, this book becomes both a media-archaeological excavation and engaging reflection on the challenges of writing media art history. The range of Kurenniemi’s fascinating practice—including electronic music composition, experimental filmmaking, robotics, and curation—defies traditional classifications, and calls for new historical narratives of media art. Started as a compilation of the long-term research that went into the exhibition of Kurenniemi’s work at Documenta 13 in Kassel, Germany, the volume combines highlights of his own writings and interviews with excellent contributions by scholars, contextualizing his archives, art, music, and vision.”

—Christiane Paul, Associate Professor, School of Media Studies, The New School; Adjunct Curator of New Media Arts, Whitney Museum

“This book is a major contribution not only to the unprecedented scientific and artistic imagination of Erkki Kurenniemi, but also to the whole research on media and ‘real time.’ The text unveils and critically presents the reader with a series of complex technological and artistic systems exploring the man-machine relationship under the assumption both do have consciousness. Kurenniemi’s work provides us with one of the most solid grounds to examine perception, the brain, the will to speculate and travel back and forth between several realms of knowledge. Kurenniemi is bold; this text is bold and a great contribution to new forms of studying risk taking in art and science.”

—Chus Martínez, Head of the Institute of Art, FHNW Academy of Art and Design

AHRC Funding for the “Internet of Cultural Things”-project

We are happy to announce that the AHRC has granted funding for our Internet of Cultural Things (IoCT) project, a one year research partnership between Kings College London, Winchester School of Art (University of Southampton), and the British Library.

The project examines the cultural dimensions of data via the born-digital material generated by the British Library, ranging from items ingested to reading room occupancy to catalogue searches. Through practice-informed research we engage this otherwise hidden cultural data, and hold a series of pop-up installations to make it visible and interfaced with the public to think through our data interconnectedness. By focusing on cultural institutions, we can move beyond the integrated operating system of the ‘Internet of Things’ and its purported productivity gains, efficiencies. Instead, we will use critical creative practice to rethink cultural institutions as living organism of data that is both dynamic and recursive. We propose the IoCT as a concept to discuss this new situation of digital data and cultural institutions.

The project starts in September 2015, and is led by Dr Mark Cote (KCL) as the PI and Prof Jussi Parikka (WSA/Southampton) as the CO-I with partners from the British Library (Jamie Andrews) and collaborating with the artist Dr Richard Wright (London).

The Warhol Forensics

The news about the (re)discovered Andy Warhol-images, excavated by digital forensics means, has been making rounds in news and social media. In short, a team of experts – including Cory Arcangel – discovered Warhol’s Amiga-paintings from 1985 floppy discs. As described in the news story: ”

“Warhol’s Amiga experiments were the products of a commission by Commodore International to demonstrate the graphic arts capabilities of the Amiga 1000 personal computer. Created by Warhol on prototype Amiga hardware in his unmistakable visual style, the recovered images reveal an early exploration of the visual potential of software imaging tools, and show new ways in which the preeminent American artist of the 20th century was years ahead of his time.” The images are related to the famous Debbie Harry-image Warhol painted on Amiga.

The case is an interesting variation on themes of media art history as well as digital forensics. As Julian Oliver coined it in a tweet:

The media archaeological enters with a realisation of the importance of such methods for the cultural heritage of born-digital content, but there’s more. The non-narrative focus of such methodologies is a different way of accessing what could be thought of as media archaeology of software culture and graphics. The technological tools carry an epistemological, even ontological weight: we see things differently; we are able to access a world previously unseen, also in historical contexts.

But there is a pull towards traditional historical discourses. The project demonstrates a technical understanding of cultural heritage and contemporary software culture but rhetorically frames it as just another part of the art historical/archaeological mythology of rediscovering long lost masterpieces of a Genius. This side still needs some updating so that the technical episteme of the excavation, detailed here [PDF] can become fully realised. Techniques of reverse engineering as well as insights into image formats as ways to understand the technical image need to be matched up with discourse that is able to demonstrate something more than traditional art history by new means. It needs to be able to show what is already at stake in these methods: a historical mapping of the anonymous forces of history, to use words from S. Giedion.

Scholars such as Matt Kirschenbaum have already demonstrated the significant stakes of digital forensics as part of a radical mindset to historical scholarship, heritage and media theory and we need to be able to build on such work that is theoretically rich.

The memoirs of an aspiring lichenologist

Rebecca Birch’s voice draws the hand drawing the landscape. It tells stories of trips and meetings, people and things. The projection of her unfolding drawing/narrating tells the story of her artwork in (auto)ethnographic style, and becomes an art performance itself. Birch’s work was recognized in Art Review’s March issue as one of the Future Greats and the magazine organised a party for her – addresses to a lichen covered stick.

A lichen covered stick was part of a particular roadtrip-performance-screening -project of Birch’s, and became the theme of the evening too. I was invited to be one of the speakers – addressing this assemblage and offering variations on the theme and Birch’s art. Below a short text based on my talk, one of several talks/performances alongside Francesco Pedraglio, Erica Scourti, Karen Di Franco and a playlist provided by Bram Thomas Arnold.

Imagine this talk voiced by an alter ego — a part real, part imagined Finnish lichenologist from the late 19th century, in his hallucinations of a future ecocatastrophy, and past earth times since the carboniferous era.

The memoirs of an aspiring lichenologist: media & ecology

In his short text about Rebecca Birch, Oliver Basciano gives us an image of her art works and refers to the capture of light as much as shadow through the role of the camera itself comparable to that stick covered in lichen.

“[the stick] acts as a sort of MacGuffin around which collaboration and conversation circle within the hermetic confines of a car. With this, one can perhaps understand the videocamera as taking a similar role – giving Birch the opportunity to embed herself in a community or situation that would remain closed otherwise”

Indeed, the stick persists as a thematic motif; it resides there as a silent interlocutor. The closed technological environment of the car hosts both human chatter as well as this stick of nature smuggled as part of the roadtrip.

The camera, the visual registers and works with light as well as lack of it – the shadow, darkness. In the context of lichen, consider another perspective too. Focus on the lichen as the first element that registers light, sound, movement, chemistry around it. It participates in Birch’s work so that it’s not only the camera, which registers the sounds and visions, but the lichen, a symbiotic organism itself. This refers to the scientific context of lichens as bioindicators – they register the changing chemical balance of the world. In short, lichen is a medium – a medium of storage, an inscription surface that slowly but meticulously and with the patience of non-human thing pays attention to the growth in air pollution. It’s symbiotic status is symbiotic in more than the biological way: it is involved in the material-aesthetic unfolding of ecologies social and nature.

It was a Finn, Wilhelm Nylander, who discovered in the 1880s details about the possibilities of using lichen as biodetectors; through experiments exposing lichen to chemical elements such as iodine and hypochlorite Nylander found out that one can “read” nature through this natural element. It meant a discovery of an important feature that tells a different story; it is less a narrative than a sensory registering of the environmental change that technological culture brought about gradually since the 19th century: atmospheric pollution, leaving its silent mark.

Lichen has over the years and years observed to be full of life and circuited as part of different ecologies. They have been not just objects of our attention, addressed by narratives and images but became part of the modern cycle of industrialised life. They silently observe our chatter, listen in, as well as through their earless senses know what we are doing to our surroundings. They provide housing for spiders and insects, but also some of lichens are (re)sourced as part of the high-tech industries for pharmaceuticals (antiobiotics) and cosmetics (sunscreen).

This participation in multiple ecologies, a cycle of different duration is a fascinating topic considering both our theme today as well as the broader discussions of past years concerning the anthropocene. In short, it is the discussion that started in contexts of geology and environmental debate about categorising our epoch as the Anthropocene – a geological period following the Holocene and branded by the massive impact humans, agriculture, geoengineering, and in general the scientific-technological culture has had on the planet. And now, it has gathered the wider scientific and arts/humanities community as part of the discussions that reflect a different , growing perspective to the environmental.

The anthropocene -and the obsceneties accelerating it as the anthrobscene – can be unfolded through lichen. In a rather important move, such Macguffins tell a hidden story of change. The technological culture in which nature becomes entangled with the human induced scientific changes. Visual, oral narratives give an image of this change. We tell stories of our nature, our interactions in ecology, in the environment with media which stores the remains of the planet as part of our human narratives- roadtrips, conversations, social events, accidental meetings, small details, landscapes – drawn by Birch in her performance that remediates the earlier.

In other words, lichen is besides a conversation piece also a medium. It saves this story through its biological means as storage that in our hands becomes memory – the scientific-aesthetic context of memory read through lichen. Even pollution becomes a sort of a mediated environment, like with photochemical smog. The lichenologist Nylander was on to something, more than observations about lichen. A lichenologist plays homage to the conversations lichen shares as it tells the story of a slow change since the coal pollution (sulphur dioxide) of England since the 18th and 19th century to the contemporary air of nitrogen compounds. So besides the conversation going on in Rebecca Birch’s car, there is this silent partner always present, as it has been for a longer while, and now also articulated in the visual arts/ecology-mix of an evening – Addressing the stick, but also: the lichen as the address which receives transmissions of industrial modern culture.

***

Nb. The party was sponsored by Absolut Vodka, with signature drinks: