Archive

OOPhotography

Congratulations to Paul Caplan who yesterday passed his viva very succesfully! These are the important moments of academic incorporeal transformation where one metamorphoses from Mr Caplan to Dr Caplan!

Besides OOO/OOP as its theoretical approach, it is a creative practice PhD, representing a very exciting addition to practice as research that relates to visual culture as well as software studies! See here for a video sample of his work and thinking (Originally in O-Zone: A Journal of Object Oriented Studies):

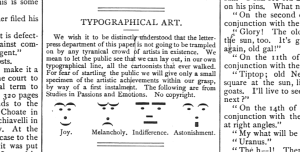

Emoticon, 1881

This article on Rhizome inspired me to post this picture relating to a sort of a media archaeology of emoticons — before the digital, before mass communication over networks, and demonstrated as a form of “typographical art”. This one is from the Puck magazine, 1881.

For a more in-depth excavation of emoticons, we should look at the various work on categorisation of emotions across humans and animals that was a key topic of research also in the 19th century. It relates to the importance of the face before the facebook.

How about the face, expression and emotion more generally? For instance Charles Darwin was interested in the evolutionary aspects of faces and expressions, and at the centre of much interest lies a curious book by the neurologist Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne de Boulogne: The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression, or an Electro-physiological Analysis of the Expression of the Passions Applicable to the Practice of the Fine Arts (1862)

Duchenne worked at the Salpêtrière hospital which later became known for its hysteric (female) patients, and the variety of new media based experiments and empirical methods by Charcot. In Duchenne’s work, the face, the expression was something that was the shared ground between humans and animals in these experiments.

Duchenne was in the 1860s using photography as a method to tap into the animal forces of the face. Photography offered him a way to capture the formal features of expressions. The patients were the models. Yet, two different time scales clashed. Photographic processes demanded a lot of time and holding the face still was difficult –Duchenne was using as his models mentally and physically ill patients. Instead of making photographic process quicker, he slowed down the body. By applying electrodes in right places of the face, the subject froze and kept the expression long enough –  it became more than a fleeting expression, and an index for scientific purposes (indeed, Darwin was using these photographs, see Phillip Prodger’s Darwin’s Camera, Oxford University Press, 2009, 81-83).

it became more than a fleeting expression, and an index for scientific purposes (indeed, Darwin was using these photographs, see Phillip Prodger’s Darwin’s Camera, Oxford University Press, 2009, 81-83).

For his own research and visualisation purposes, Darwin used engravings made from the photographs, where the electrodes were removed. This made the expressive faces slightly more natural, of course. An enforced typology of the face and emotion.

A Media Archaeological Office

Not every professor has an office like this. Peep into Erkki Huhtamo’s (UCLA) media archaeological office through this video, and get a taster of his enthusiasm as a collector: zoetropes, mutoscopes, kinetoscope. It demonstrates the curiosity cabinets of media history but also the need to train specialists who are able to maintain these instruments as part of the living heritage of media cultures outside the mainstream. The devices prompt us to ask questions concerning difference: how different media culture could be, and has been.

The video is a good insight to the just released Huhtamo book on the moving panorama: Illusions in Motion, just out from MIT Press.

The Photosculptural Hypothesis

3-2-1- A whistle blows and 24 shutters go “click”. Again, with a different model, head help up straight and still by a support.

3-2-1- A whistle blows and 24 shutters go “click”. Again, with a different model, head help up straight and still by a support.

3-2-1 the whistle blows. Click-click-click-click…

It’s image making but not just photography – instead, it provides an alternative route for histories of media; instead of a preference for the centrality of the seriality of the moving image, try starting from the cybernetic. “The cybernetic hypothesis”, as Alex Galloway coined it in his talk at the Winchester Centre for Global Futures that was a kick-starter for the project.

The whistle, the 24 cameras, set around a circular studio, a rotunda on which a stool for the model – an assemblage that connects the early 1860s with the 2012 reconstruction inside which I too sat to be photographed, and to be sculpted from those 24 shots. Originally this was Francois Willeme’s photosculpture, a curious arrangement and a patent from 1860s Paris that defined what Galloway calls one early model for parallel media.

Winchester School of Art Fine Art undergraduate students took up the original blueprints and the idea as their own model for a project led by Ian Dawson and Louisa Minkin and produced a fantastic remake of the Willeme-device. Inspired by Alex Galloway’s talk, and partly framed as a media archaeological project, it presents indeed a very inspiring way to address sculpture, parallel imaging and informational culture. Like so many media archaeological art works, it suggests how you can presence old media ideas – often not very mainstream – in current settings; like taking an alternative viewpoint not only to media art history, but also to current image cultures.

The photosculpture – which indeed as sculptural mediates the imaging into physical three dimensional objects and presents a sort of an archaeology of 3-D digital imaging/modelling – shifts our perceptual coordinates. It forces itself as a rather (in a good way) weird part of the cultures of digital imaging with its historically “out-dated” way of understanding media. That is the beauty of the device and the arrangement; it is a historical and media archaeological exercise in practice-led activity that investigates the conditions of visuality and perhaps even cybernetic culture, as Galloway claims.

“A sculptor and the sun will become collaborators working together to fashion in 48 hours busts or statues of a hitherto unknown fidelity of such great boldness in outline and admirable likeness.” Those were the words of the journalist Henri de Parviel, describing the original piece by Willeme. You can see how it describes the emerging business in quickly produced, sculpted visuality – a bust in “admirable likeness” in no time! The WSA project taps into the way in which visual technologies were starting to be mobilized into consumer products and services, but old media ideas can be cheap R&D too (to use the phrase by Garnet Hertz) for artistic ideas and reappropriations, and engage with the multiple medialities that our media technologies consist of: it’s not only about the photographic visuals, nor just sculpture, nor just a genealogy of the informatics, but a folding of various medialities. Even a single technological assemblage and practice can contain so much, as the project demonstrated. Media are never about single objects, devices or apparata – but a multiplicity of techniques and technologies assembled. Hence, a hands on assembling is itself a process of thinking through this multiplicity of media and arts apparata in order to get a sense of the delicate materialities and techniques which they enable, and how they are themselves enabled.

(For further reference, a film from 1939 from the Pathe archives, with Marcus Adams in his studio demonstrating the photosculpture)

WSA MA Students’ Final Show

Opening on the 30th of August, 5 pm, at the Winchester School of Art campus!

Beauty of the Panorama

Much waited for… and soon out, Erkki Huhtamo’s massive study on the moving panorama: Illusions in Motion. Media Archaeology of the Moving Panorama and Related Spectacles.

Forthcoming from MIT Press, watch out for this book by the leading media archaeologist. It really is such a meticulous study and massive source base through which he investigates one possible way to understand visual media culture. Oh and it’s a beautiful book, filled with images, nicely composed as part of the text.

I also endorsed the book for it’s back cover:

“Pioneer of the media archaeological methodology, Huhtamo reveals in this book his roots as a cultural historian. Illusions in Motion is painstakingly well researched and meticulously composed. Besides excavating the histories of this neglected medium, the moving panorama, it offers an empirically grounded example of how to research media cultures. Huhtamo shows us what fantastic results patient research can achieve.”

The Media That Therefore We Are – on Lenore Malen’s video installation

I wrote this short catalogue text for Lenore Malen’s I am the Animal — also included stills (courtesy of and permission from Lenore Malen) from the exhibition:

The Media That Therefore We Are

It’s a matter of scales. If you are far enough away, and your perspective is mediated by a layer of concepts, abstractions, and an organizational eye, you might indeed see them as models of ideal society. It’s all order. Everyone does what they are supposed to. There is one Queen. No wonder the protofascist Maya the Bee was an ideal cartoon character for 1930s national-socialist Germany. One is tempted to see the idea of a strong leadership to which everyone submits as an example of sovereign power per se, even if, to be honest, the Queen does not choose to execute power — it happens much more intuitively, almost in a subconscious way. Of course, when it comes to bees, there is no such talk of subconscious; instinct used to be the word in the 19th century for this near mystical mode of organization. This is evident in, for instance, Maurice Maeterlinck’s The Life of the Bee (1901), which refers to “the spirit of the hive.”

But on another scale, it looks very different. Look closely enough and they become the aliens they are: their weird compound eyes composed of thousands of lenses, their six legs, non-human movement, jerky, non-mammal insides folded out. This has been the other story since the 19th century and the birth of modern entomology: insects as aliens, otherworldly non-humans, often seem almost to possess technology in their capacities to see, sense, and move differently. The insects are the Anti-McLuhan; technics does not start with the human but with the animal, the insect, and their superior powers of being-in the- world (the allusion to Heidegger is intentional).

Lenore Malen’s I Am The Animal intertwines the various histories, aesthetics, and idealizations of the bee community as well as the bee’s relations withbeekeepers. It’s all about relations, and establishing relations with our constitutive environments — including bees. Donna Haraway talks about companion species (specifically dogs, but other animals too) as formative of our being in the world; she discusses the ways in which those relations are formative of our becomings.

Lenore Malen’s I Am The Animal intertwines the various histories, aesthetics, and idealizations of the bee community as well as the bee’s relations withbeekeepers. It’s all about relations, and establishing relations with our constitutive environments — including bees. Donna Haraway talks about companion species (specifically dogs, but other animals too) as formative of our being in the world; she discusses the ways in which those relations are formative of our becomings.

Our relation to insects is reflected in much more than the narrative aspect of Malen’s work. The immersive environment of the installation envelops the spectator in a milieu of becoming. The clips Malen uses are mini-thoughts, mini-brains, which are brought together with her digital software tools; the clips are memes that Malen excavates from online archives and audiovisual repositories, and composes into a three-channel envelope.

I Am The Animal poses the question: Can insects be our companion species? This is paradoxical in light of Derrida’s The Animal That Therefore I Am, to which Malen’s title refers. Derrida starts with the gaze of the animal — his cat, to be exact, lazily gazing at Derrida’s naked body. But catching the insect’s compound eyes is more difficult, if not impossible. For Malen, Derrida’s essay functions as a critique of subjectivity. Derrida continues to analyze how the cat does not feel its own nakedness, has no need of clothes, whereas we — as technical beings — surround our bodies, envelop ourselves in extensions, such as clothes. We are not only enveloped in cinema, media, and technology but in fundamental forms of shelter.

So do animals have technology? They might not plan buildings and produce external tools, but an alternative lineage claims that animals, insects and such, are completely technical. Henri Bergson was of such an opinion: even if humans are intelligent in the sense of being able to abstract, plan, and externalize their thoughts into tools, insects occupy technics in their bodies and embody intertwining with the world. The body itself is already technical. One could think of examples of insect architecture, of various stratagems of the body for defense or attack, of modes of movement, and of perception as media. If the body is media — as Ernst Kapp suggested in the 19th century and McLuhan later — then what kind of media does the insect suggest?

The three screens of I Am The Animal are rhythmic elements that deterritorialize our vision. A slowly progressing multiplication of viewpoints is the becoming-animal of perception that the installation delivers. The immersive space is also one of measured fragmentation into the compound vision of insects. Slow disorientation is one tactic of this mode of becoming; it points both to the world of insects and to the media in which we are immersed. The early avant-garde connection between the technical vision machine and the insect compound machine — in the words of Jean Epstein, “the thousand-faceted eyes of the insects” — creates a sense of space as split; perspective is multiplied into a variation. Malen’s I Am The Animal is about such forms of multiplicity.

The animal is incorporated into the machinated cultural assemblages of modernity; the disappearance of animals from urban cultures during the past couple hundred years is paralleled by the appearance of animals in various modern discourses from media to theory. We talk, see, incorporate animal energies. Akira Mizuta Lippit in Electric Animal (2000) writes how “the idioms and histories of numerous technological innovations from the steam engine to quantum mechanics bear the traces of an incorporated animality. James Watt and later Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, Walt Disney, and Erwin Schrödinger, among other key figures in the industrial and aesthetic shifts of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, found uses for animal spirits in developing their respective machines, creating in the process fantastic hybrids.”

Animals as well as media are elements with which we become. Matthew Fuller in his essay “Art for Animals” (2008) identifies a two-fold danger in relation to art with/about nature: that we succumb to a social constructionism or that we embrace biological positivism. And yet, we need to be able to carve out the art/aesthetic in and through nature and animals in ways that involve the double movement back and forth between animality and humanity. Art for animals is one way, to quote Fuller: “Art for animals intends to address the ecology of capacities for perceptions, sensation, thought and reflexivity of animals.” What kind of perceptions and sensations are afforded us by media/ nature? And conversely, what worlds do we create in which animals and nature perceive, live, and think?

Winchester Speaker Series: Phillips and Milne

We are today kicking off our new research centre seminar series with John Phillips (National University of Singapore) and his talk “Seeing Things” – which promises to address Bernard Stiegler, military technologies and critical theory.

And next week Thursday, continuing with Esther Milne with Siegert, not Stiegler!

THE WINCHESTER CENTRE FOR GLOBAL FUTURES IN ART, DESIGN & MEDIA

Seminar Series: 3 November 2011, 5 pm at seminar room 8-9.

‘Technologies of Presence: Intimate Absence and Public Privacy’

Esther Milne

Intimacy, affect and image are always intertwined at the level of technology. The practices of mail-art, for example, are enabled by the material conditions of the postal exchange. In turn, the economies of this exchange are underpinned by the dance between absence and presence: writing a letter signals the absence of the recipient and, simultaneously, aims to bridge the gap between writer and recipient.

This paper traces the production of presence across nineteenth century postal networks in order to make some preliminary remarks about twenty first century platforms of social media, such as Twitter. In particular it explores the emergence of contemporary patterns of ‘public privacy’ through their socio-technical historical settings. Postcard media offers one such site. As Bernhard Siegert and Jacques Derrida have demonstrated, the postcard operates as a liminal figure for the reformulation of public and private communication.

‘Public Privacy’ describes the ways in which subjects use the public signifying systems of social media to produce images of love, desire and pain. Yet such rhetorical strategies are not unique to distributed digital platforms. After all, the eighteenth century epistolary network, often called ‘The Republic of Letters’, was responsible for reconfiguring the public and private domain. Through an exploration of mail-art practice, this paper identifies the postal principle of Twitter to challenge recent claims for the ‘death of privacy’.

BIO: Dr Esther Milne is Deputy Head of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences at Swinburne University, Melbourne, Australia. She researches in the areas of celebrity production within legislative and cultural contexts; and the history of networked postal communication systems. Her recent book, Letters, Postcards, Email: Technologies of Presence, is published by Routledge.

WSA MA Degree Show 2011

My new job at Winchester School of Art – and the students graduating of the 2010-2011 courses – is having its annual Masters Degree show. Chuffed about this. Includes a wide range of expertise from fine art to communication design, (advertising) design management to fashion and textile design.The Degree show kicks of September 1st with a Private View.

WSAMA 2011 launch and private view = 01/09/11 1800-2000 HRS

(Warning: the video has strong flicker).

For more info (and no-flicker), see the blog at http://wsama.wordpress.com/.

The Physicist of Media Theory – Friedrich Kittler’s Optical Media

Oops. I should have done this a long time ago, but better late than never. Anyhow, it took several years anyway before it came out in English – Friedrich Kittler’s Optical Media (Polity Press 2010, orig. 2002) – so a little delay in writing about the translation does not hurt.

took several years anyway before it came out in English – Friedrich Kittler’s Optical Media (Polity Press 2010, orig. 2002) – so a little delay in writing about the translation does not hurt.

It would be tempting to emphasize the radical alterity of the “Kittler-effect” (as named by Winthrop-Young) in relation to the more standardized and domestic Anglo-American discourses in media and cultural studies. Even the word “studies” is an abomination for Kittler, who is of the German tradition where “sciences” is still the word for humanities too. For Kittler, this is to be taken to its hard core: sciences stand at the centre of arts and humanities in the age of technical media, and a failure to take this into account would be like a bratwurst without sauerkraut. Nice, but not really the real thing.

This is one of the crucial points that a “German perspective” to media studies has promoted: media are not only the mass media of television, newspapers and such, but a technical constellation that at its core is based on scientific principles of coding, channeling and decoding of signals. When Kittler says the lectures (Optical Media is based on a lecture series he gave at Humboldt University, Sophienstrasse, Berlin, in 1999) are an investigation into man-made images, we should remember his earlier predisposition and tendency to talk of the “so-called-man. Kittler is after all a sort of a Foucault of the technical age (as also John Durham Peters in the foreword notes, instead of the usual label of Kittler as the Derrida of the digital age). Man is a temporary solution, a crossroad in the complex practices and epistemologies of knowledge that might (has?) proved to be not so useful anymore when media can communicated to each other without human intervention. Ask your plugged-in Ethernet cable, it knows the amount of data that goes through it without you pushing even a single key (as Wendy Chun reminds us in her Control and Freedom).

Kittler’s hostility towards any human-centred history of invention is well summed up for instance in this quote:

“And when Liesegang edited his Contributions to the Problem of Electrical Television in 1899, thus naming the medium, the principle had already been converted into a basic circuit. Television was and is not a desire of so-called humans, but rather it is largely a civilian byproduct of military electronics. That much should be clear.” (208)

That much should be clear, right? And Kittler is a techno-determinist, right? Well, as Winthrop-Young has in his wonderful little intro Kittler and the Media articulated, this judgment seems to be worse than claiming that someone enjoys strangling cute puppies, and hence needs no more than the accusation – whereas exactly this point needs elaboration. I am not promising to do that in this review, but just a quick point. One thing that we need to remember is that for Kittler, media are about science and engineering, and some of the confusions relate to how people are trying to read and apply him out of those contexts. Calling someone techno-determinist when he has continuously underlined that this is what he does – investigates the engineering aspects of media – is, well, redundant. Naturally this does not solve the whole question, but at least points to something we need to keep in our minds when reading Kittler.

His media theory is not about the media as interpreted, consumed and produced by creative industries, digital humanists, or such, but about the long genealogies of science, engineering and the qualities of matter that allow the event of media to take place. Media is displaced from McLuhanite considerations to “where it is most at home: the field of physics in general and telecommunications in particular.” Kittler is the physicist of media theory.

Optical Media is in that sense reader-friendly (if Kittler ever is) that it takes as its clear methodological point of departure Shannon’s communication theory. Slightly anachronistically Kittler transposes this as a model to understand media history. How coding, channeling and decoding takes places in material channels that are surrounded by noise.

Kittler’s Optical Media has several problematic statements, exaggerations and mistakes too – some of which the translator Anthony Enns has picked up on and made corrective notes. In other ways too, the translation is excellent, and presents us with a Kittler that is smooth to read. Translating Kittler is not easy, and much gets lost in translation but Enns is excellently equipped to present us media theory that is vibrant and readable.

It will be interesting to see how Kittler’s impact will be continued. Despite the rhetorical distanciation from US and UK that one encounters in this Sophienstrasse brand of media theory – which is wary of the Bologna Process of education standardisation in Europe threatening academic freedom, of Anglo-American monetarized neoliberal discourses of knowledge, and the general forgetting of old Europe and its philosophical traditions – recent years of English speaking media studies picked up at least indirectly from material media theory. Such ways of making sense of technical media are visible in software studies, platform studies, digital forensics à la Matthew Kirschenbaum and other recent, exciting theory debates. Kittler is being read. We don’t need a Kittler-jugend as Winthrop-Young has pointed out, but Kittler-effect is hard to escape; the big question is how to take that forward to as innovative directions as Kittler produced.

What is interesting is that the lack of German language in Anglo-American circles has produced a situation where most scholars are reliant on translations (I am glad to see Polity Press putting out Kittler-related literature). Hence, a lot have also missed the “turn” Kittler has taken during the past 10 years from war to love. The writer of post-humna media theory talks about love, sex and Antique Greece in his magnum opus project that could be summed as the attempt to place Jimi Hendrix (Electric Ladyland, And the Gods Made Love) in the age of Homer. The other Homer than a representation analysis of Simpsons’ Homer.

Notes:

1) Disclosure statement: My own new book is also contracted with Polity Press – Media Archaeology and Digital Culture (2012)

2) Friedrich Kittler’s last talk at the Sophienstrasse 22 address, Berlin. The Institutes are moving premises during summer 2011.