Archive

On Air, Inhale

I had the pleasure of contributing to Tomas Saraceno’s new show On Air at Palais de Tokyo with a short text for the publication as well as with a talk as part of the seminar on December 14th, which was organized by Filipa Ramos. The show itself moves from spiders and webs to air and balloons, from entanglements of the Anthropocene to the light materials of the Aerocene combining speculative design, investigation of materials and beautiful installation structures.

My short text for the catalogue was titled “Inhale”:

Inhale and you engage with history, not metaphorically, nor poetically but literally. Inhale the air of a city and you inhale its industrial legacy, its current transport system, its chemistry built at the back of technological progress. There’s more in the air and the sky than meets the eye. On the level of eyes, nostrils and skin, the city and its surroundings, it becomes a touch. It is inhaled, enters the body as haptic environment. It is the haptic environment in which one sees and encounters the surroundings as a large scale Air-Conditioning Show. It is history carried forward as chemistry. It is technology breathed in as minuscule particles. The air is the environment we have to somehow learn to address as one way to invent a breathable future.

The Elastic System launches online

Richard Wright’s art project the Elastic System has launched now online too. Originally commissioned as part of our AHRC funded project Internet of Cultural Things, the piece was first a temporary installation at the British Library (and subsequently touring to Hartley Library, University of Southampton where it was presented with support from Dr Jane Birkin and AMT). Please find below the Press Release for the online launch. I myself am currently writing a text on art practices, library infrastructures and contemporary cultures of data in cultural institutions.

***

Press Release

Follow: https://twitter.com/ElasticSystem

You are invited to visit the new high resolution version of the ELASTIC SYSTEM, an artwork by Richard Wright in collaboration with the British Library.

The ELASTIC SYSTEM was produced during a year-long artist-in-residency at the British Library and is the first artwork to be given access to their core electronic networks and databases.

The work takes the form of an interactive portrait of the C19th librarian Thomas Watts, an obscure but important figure in the early history of information technology. In 1840 Thomas Watts invented his “elastic system” of storage for the British Library to cope with the enormous growth in their collections that was threatening to overwhelm them. This photomosaic has been generated from 4,300 books as they are currently stored in the Library basements at St Pancras, an area not normally accessible to the public. The “Elastic System” functions like a catalogue, allowing people to visually browse part of the British Library’s collections, something which has not been possible since Watts’ time. Furthermore, each book is connected live to the Library’s electronic requesting system. By clicking on a book you can find out more about the item and how to request it from the Library. If you do request a book, it is removed from the mosaic to reveal a second image underneath. This image is a portrait of the staff who work in the underground storage basements, the hidden part of the Library’s modern requesting system.

In order to create the second image, the artist spent two days working with the basement staff at the St. Pancras site, taking hundreds of photographs. With a collection as large and as diverse as the British Library’s, its successful functioning depends on a well tuned human element, which although it is as essential as the electronic networks, is less visible and less appreciated.

After being exhibited as an installation at the British Library, the Hartley Library and the Digital Catapult centre, the “Elastic System” has now been optimised and rebuilt at double the resolution. It is being released as a public web site on September 9th to mark the anniversary of the death of Thomas Watts in 1869.

This work is part of an AHRC funded research project called “The Internet of Cultural Things”, a partnership between the artist Richard Wright, Dr Mark Cote (KCL) and Professor Jussi Parikka (Winchester School of Art) with wide representation from the British Library including Jamie Andrews, Head of Culture and Learning, Dr Aquiles Alencar Brayner and Dr David Waldock. The aim is to use digital data and the creative arts to transform the way people and public institutions interact. The “Elastic System” uses Watts early C19th insights into database access to create a new catalogue out of visual metadata (digital photographs), making it a portrait that is also an extension of his work.

Richard Wright is an artist working in animation, moving image and interactive media. An archive of his work can be found here: www.futurenatural.net

Email: contact@elasticsystem.net

The artist has written three blog posts about their research behind this project:

https://internetofculturalthings.com/2016/06/08/where-is-the-library/

https://internetofculturalthings.com/2016/06/18/what-can-you-do-with-a-library/

https://internetofculturalthings.com/2016/09/01/elastic-system-how-to-judge-a-book-by-its-cover/

Google Photos: https://tinyurl.com/ElasticSystem-images

Thousands of Tiny Futures

Below is a text I was commissioned to write for the Seoul Museum of Art(SeMA)’s exhibition “Digital Promenade: 22nd Century Flâneur” for the 30th Anniversary of SeMA. The text will be out soon in their catalogue but here is already the (not copyedited) version online for those interested.

Thousands of Tiny Futures

0 Ruinscape

To state the obvious: the interesting thing about future or futurisms is not really about the future but the operative sense of this temporal tense. The now and here of the work of futurisms is inscribed in words, images and sounds; it is painted as landscapes and visible in such traces that constantly expand the particular living and breathing space of the present. Future is involved in forming what the now is, and even more so, what times are our contemporaries.

Times are entangled and switch places; markers of fossilised pasts appear as imagined indexes of futures too. Future fossils – a topic that ranges from the 19th century geologists and popular culture to contemporary imaginaries of a projected sense of now – comes out in other ways than merely ruins of contemporary landscapes of consumerism. Why are so many artistic and popular culture examples of future landscapes of fossils an imaginary of a future that repeats the trope of its own invention – that is, the modernity of technological objects that defined its start are also the defining features of its seeming end? As such, it is a recursive imaginary that merely tells what we knew already since Walter Benjamin (1999, 540) at least:

“As rocks of the Miocene or Eocene in places bear the imprint of monstrous creatures from those ages, so today arcades dot the metropolitan landscape like caves containing the fossil remains of a vanished monster: the consumer of the pre-imperial era of capitalism, the last dinosaur of Europe.”

Instead of the cyber cool aesthetics of future fossils of technology that merely returns to the consuming human subject of digital gadgets, consider what times are we living in now: times of toxic ecologies in which the future tense takes different forms for different forms of life (cf. Tsing et al 2017). Consider futurisms and the temporal imaginaries not purely as the solitary “when” but as the contemporary question of where and to whom? What sites are identified as part of this futuristic pull, where are futures placed, how are they inscribed in contemporary cityscapes and landscapes as if signs of things to come? What else besides the Blade Runner styled Asian cities are indexical of what counts as future (Zhang 2017) – and what else than remnants of the visible markers of technological now of gadgets is significant in terms of this out of place of a future present?

Hence, a shift in focus: away from a fetishisation of future that inspires the Anthropocene-led aesthetics of future ruinscapes [Note: a point also raised in Joanna Zylinska’s Nonhuman Photography book] towards an analysis and art of contemporary signs and images. These ruinscapes involve imagining what time is this place in and where it lies and is it seen from. A good example would be Point Nemo, a region in the South Pacific pretty much more imagined to most than actually visited by almost anyone. And yet, it is perhaps one of the most apt sites to consider as a fossil site: it is where the international space agencies are dumping much of their retired space technologies, in no man’s waters, also coined “the least biologically active region of the world ocean” (in the words of oceanographer Steven D’Hondt ) because of its remote location and particular rotating current. With its lifeless bottom of an ocean, with dumped technologies from Cold War to the current day practices, it seems a likely site for a future fossil ruinscape very much existent now – as undramatically invisible as the disappearing ice that defines the transformation of much of planet’s expected future.

No mountain of garbage for art photography and the white cube, no site of exquisite trash and remnants of most familiar everyday things, but just the disappearance on the seabed, and the disappearance of ice – the future arrives as a temperature shift.

This short text engages in this topic through figures or fields of time that are also visible in contemporary media theory and art practice: archaeologies, futurisms and futurities. All of the briefly discussed themes relate to different ways of engaging with time and futurity, with fossils and fossil fuels, including the ones that are predicted as part of constant financial speculation on the energy market. The past was already a fossil that determined the mess we are in.

I Archaeologies

At first thought, it is somewhat odd to assume that archaeology – or media archaeology – would have anything to say about futures and futurities, only about the past. The way in which archaeology has for a long time referred to much more than just the specific discipline is here however the significant cue: archaeology has infiltrated philosophy and the humanities from Immanuel Kant to Sigmund Freud to Walter Benjamin to Friedrich Kittler and contemporary media archaeologies and presents itself as more than a specialised discipline. As Knut Ebeling (2016, 8) argues, these various philosophical and artistic wild archaeologies present not merely an image of layered pasts but they become sites of practices of experimentation with “a material reflection of temporality that began in the 18th century and reached a definite climax in the 20th century.”

The epistemological figure and field of archaeology becomes then less a complementary sidetrack to the work of history than its alternative: instead of narrating, it counts, instead of text, it applies to the other sort of modalities of materiality as sound, image, number, which is also why it has become the preferred term for so many media theorists. Furthermore, as Ebeling continues referring to Giorgio Agamben, the archaeologist maps what is originating, what is emerging and what is productive of new temporalities. It becomes a map of times of different sort, which often are recognize as stretched between the layers of the past and their effect on the present, but what we could also develop into the recognition how they issue different potentials of futures.

Archaeologies are also maps of futures – or more likely, they complexify the linear temporal coordinates as past, present and future. Media archaeologies work with a different set of physics than any assumed simple causality (cf. Elsaesser 2016), which is likely one of the explanations why it has become such an interesting field of resources for artistic work too. Not just the materials of the the quirky retropasts, but the subtle definitions and search for other times in which media from cinema to AI is also part of production of that time.

In this context the media archaeological perspective to fossils would not be merely about searching for an image of a future fossil, but to understand how the image itself is premised on the existence of fossil fuel. While the technical image from the photograph to the cinematic is according to Nadia Bozak (2011, 29) the perfect crystallisation of how we, in her words, capture, refine and exploit the sun, it is also the sun energy in fossil fuels such as oil that mobilizes the industrial culture of which technical media is one part. Bozak refers to the wording by Alfred Crosby that oil is the “fossilized sunshine”. This wording is an apt start to establishing the link between energy and the particular different sort of mobilization of light and sun that we can speak of as practices of visual culture (cf. Cubitt 2014). The first fossils are, then, the images and the fossils are also imprints. There is a surprisingly tight link between the history of technical images and the history of mobilization of fossil fuels, which also Bozak (2011, 34) observes:

“The relationship between sun and cinema, light and the film environment, is especially apparent when cinema is juxtaposed against current environmental rhetoric, which ultimately fuses the fossil fuel with the fossil image, both manifestations, mummifications, of captured light.”

The forms of energy and their forms of capture as technical media present a new time – both in the sense of technical media time, and in the sense that pertains to the massive changes in environmental conditions of living in contexts of the capitalocene.

II Futurisms

If future fossils were already embedded in the history of fossils as fuel, what becomes of our task to map the different technological futures? Futurisms in 20th century art have a particular relation to technology. The Italian futurists are located at a very particular phase of European history and a very particular machine aesthetics that offered a one temporal sense of progression by way of technological progress. This aesthetic became one recurring reference point to how futures are visualised, sonified and written as poetry in the age of mass-scale industrial systems including electricity and electric light. Energy is not merely represented but imagined as the motor of the aesthetic expression – it becomes its motor of imaginaries (cf. Bozak 2011, 38). It is the city, the urban sphere that was for the contemporary Benjamin also the start of the ruinscape, again later ruined in the bombed down European cities, a form of technical change and planning replicated in many other forms across the planet since the “Great Acceleration” of the Anthropocene post-1950s.

Of course, the later (art) futurisms take a different tone that is less the masculine, celebratory stance of a future that should arrive as progress, but a writing of a future that was never allowed or the future that was imposed. It is in such political archaeologies that Afrofuturism and many later ethnofuturisms (as they are sometimes coined) emerge. Whatever the collective term might be, Afrofuturism, Sinofuturism, Gulf Futurism, Black Quantum Futurism and other current versions speak of the multiplication of futures in contemporary art and visual culture (Parikka 2018). Some of it feels like future overturned. For Gulf Futurism, and in works by artists such as Sophia Al Maria, the placement of a future that already arrived is read against the backdrop of the architectural built environments in the Arabian Gulf states. The artificial environments that work both horizontally and vertically as significant elements coined also as Dubai Speed (Bromber et al. 2016: 1) speak of one particular version of capitalist futures. Built from oil and fossil pasts, such cities and environments necessitate imaginaries of the future: how are architectures, building materials and infrastructures primed at the back of fossil fuels for a post-fossil life? While a key archaeological question for Walter Benjamin was how to read the city through its fragments as a slow emergence of capitalist consumer culture, the current version in such situations is how the city is imagined towards a future while trying to deal with that industrial legacy and its toxic environments.

Gulf Futurism and other artistic futurisms are, in many ways, artistic discourses in this context of toxic environments. Toxicity of course comes in many forms, where chemical toxicity and political pollution go hand in hand. (Guattari 2000). But how does one then imagine in visual arts and in visual forms the style of pollution that is subtler than mere piles of rubbish? The cultural techniques of environmental monitoring are already rather an important form of visual arts in how they make invisible traces perspective and part of matters of concern (Latour 2008). Hence the sort of contemporary arts about air pollution and chemical waste, about radio activity and the loss of biodiversity speak of modalities and scales that otherwise would not be included in registers of futurisms now. Any adequate futurisms need then to be able to deal with the invisibilities that are the ontologically urgent side of what counts as slow violence (Nixon 2013). Hence the future tense in the aesthetic and artistic sense needs to be capable of rather radical detachment from the usual dreamy anthropocentric narratives of worlds without humans, and to engage with contemporary cultural processes that already are without humans. What’s more, the forms of futurisms all speak to the mentioned meaning of archaeology for Agamben: production of new times.

III Futurity

Lawrence Lek’s recent work on Sinofuturism and Geomancer picks up on the futurist trope but places it in different geographical regions and with a different centre of subjectivity. Furthermore, Geomancer’s CGI film protagonist is an AI instead of the usual human narrator. The AI dreams speak of different worlds and of different modalities of art than ones with a voice or hands could have. The calculational dreams of an AI system are viewed as part of a total memory and calculation system that itself is not only an imaginary of a future but one that prescribes a way to think futurities as a contemporary cultural technique. These are futures that are constantly counted into existence than merely narrated into imaginaries.

The mobilization of AI systems in multiple areas of industry and culture is emblematic of what future now means as calculation. Consider then the future image as one that is future in the most limited sense and yet effective in the most widespread sense: the mobilization of various datasets from satellites to ground remote sensing, from media platforms to urban smart infrastructures as part of the training of AI algorithms and predictive measures. For example satellite data on ground level changes – infrastructures, buildings, urban growth, agriculture and crop yields – can be fed into machine learning systems with the aim of predictive data that can feed into for example financial predictions. The temporality of data is here key to understanding the little futures that are constantly created in machine learning and in financial contexts, and with most effective turbulence in terms of the futures market (see Cooper 2010). The machine learning of prediction of surface changes on global datasets or the prediction of real time changes in video feeds such as in experiments with neural nets like Prednet are good examples of the very local techniques useful for an image of a future one step ahead. Recently Abelardo Gil-Fournier has engaged with these machine learning platforms, farms and techniques as part of his investigation about the operative image in relation to earlier forms of operative light, as in industrial agriculture. Furthermore, this resonates well with the wider picture painted by Mark Fisher and Kodwo Eshun (2003: 290) writing on SF (science fiction) capital based on the various forms of futurism:

“[it] exists in mathematical formalizations such as computer simulations, economic projections, weather reports, futures trading, think-tank reports, consultancy papers—and through informal descriptions such as sciencefiction cinema, science-fiction novels, sonic fictions, religious prophecy, and venture capital. Bridging the two are formal-informal hybrids, such as the global scenarios of the professional market futurist.”

Futures exist as constant reference points for models, and unpredictable patterns or events are attempted to be constantly “factored into the calculations of world economic futures” (Cooper 2010, 167). Hence, also the unruly non-linear dynamics of any natural system are in this sense not anomalous but merely turbulent and as such material for the various ways different futures can be created, including accounting for the environmental crisis as one part of the work of management (Cooper 2010).

From future fossils and apocalyptic far or near futures scenarios as imaginaries we shift to the technological counted futures that are the standard operating procedure of financial markets. It is in this sense that the work of futurisms and creating new temporalities are somewhat paralleled by these tiny futures that are the constant business of the market. This proves the point that imaginaries of futures are not inherently or necessarily anything progressive in the sense of addressing planetary scale justice, but need to be complemented with the analytics, aesthetics as well as imaginaries of counter-futurisms (cf. Parikka 2018) – the work of not merely dreaming but creating infrastructures that imagine and count for our benefit.

References

Benjamin, Walter 1999. The Arcades Project. Trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Bozak, Nadia 2011. The Cinematic Footprint. Lights, Camera, Natural Resources. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Bromber, Katrin, Birgit Krawietz, Christian Steiner, and Steffen Wippel. 2016. ‘The Arab(ian) Gulf:

Urban Development in the Making’. In Steffen Wippel, Katrin Bromber, Birgit Krawietz and Christian Steiner (eds), Under Construction: Logics of Urbanism in the Gulf Region. London and New York: Routledge, 1–14.

Cooper, Melinda 2010. “Turbulent Worlds. Financial Markets and Environmental Crisis”. Theory, Culture & Society vol. 27 (2-3), 167-190.

Cubitt, Sean 2014. The Practice of Light. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Ebeling, Knut 2016. “Art of Searching: On ‘Wild Archaeologies’ from Kant to Kittler. The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics No. 51 (2016), pp. 7–18

Eshun, Kodwo 2003. “Further Considerations of Afrofuturism”. CR: The New Centennial Review 3:2, Summer 2003, 287–302.

Latour, Bruno 2008. What is the style of matters of concern? Amsterdam: van Gorcum.

Nixon, Rob 2013. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Parikka, Jussi 2018. “Middle East and Other Futurisms: imaginary temporalities contemporary art and visual culture.” Culture, Theory and Critique, 59:1, 40-58,

Tsing, Anna; Swanson, Heather; Gan, Elaine and Bubandt, Nils, eds. 2017. Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press.

Zhang, Gary Zhexi 2017. “Where Next?” Frieze, April 22, 2017, https://frieze.com/article/where-next.

Oodi Art Project: AI and Other Intelligences

As part of our curatorial project on Library’s Other Intelligences we received an exclusive sneak preview of the new Helsinki Central Library, Oodi. With Shannon Mattern, Ilari Laamanen (Finnish Cultural Institute New York) and our artists we were able to see how the insides are shaping up. The aesthetically and architecturally stunning building is also such an interesting cluster of spaces that one could write about them much more extensively than just a this short posting. That longer piece might follow later, but already now I personally was struck how they deal with media in its multiple forms from analog to digital, from projection to making. From a cinema theatre equipped with also 35 and 70 mm projecting opportunities to a bespoke space for an analog synthesiser, the library offers an amazing platform for a public engagement with media which also includes recording studio space and a maker space – and yes, even a kitchen. The library is catered as a space of media transformations. At the moment the building exposed its multiple wires, cables, ducts and work – the labour of construction as well as cleaning that is already going on for the launch in December.

The top floor is reserved for what one would imagine as the “traditional” library, a space for books and reading, which also opens up to a terrace overlooking the Finnish parliament building. The roof wave is pretty stunning.

I wanted to include some of the visual impressions from the space that shows its infrastructure being built up, a theme that is present in some of the works from the artists Samir Bhowmik, Jenna Sutela and Tuomas A. Laitinen. In general, a key theme of our project concerns architectures and infrastructures of intelligence – both engaging with AI but as an expanded set of intelligences from architectural intelligence to ambient intelligence, from acoustics to amoebas and others layers of an ecology of a library that is a life support system – biologically, intellectually and culturally. It’s these multiple AIs that define the generative forms of languages, materials, and new publics that are present in how we want the space to be perceived. The exhibition opens in January 2019. Updates on social media will use the hashtag #OodiIntel.

MUU/Other

I am very excited to announce that I have been awarded Honorary membership of the MUU media artists’ association (Finland). Celebrating its 30th anniversary, MUU (Finnish for “other”) has become renowned for its pioneering work in supporting media and experimental arts in Finland. Needless to say, it is a big honour for me to be included in their roster of honorary members. Here’s the picture of my head receiving the award today.

The Library’s Other Intelligences

We are happy to publicly announce our art and curatorial project The Library’s Other Intelligences! Together with Shannon Mattern we are curating a show in Helsinki that includes three inspiring artists Jenna Sutela, Tuomas Laitinen and Samir Bhowmik who all engage in their work with the ecologies intelligence – artificial, artistic, ambient, architectural – that define the library as a cultural institution of knowledge. A key aspect of the project is that it is set as part of the new Helsinki Central Library Oodi – opening its doors in December.

The show opens in January and you can read more information here and if in Helsinki next week, please attend our event Alternative AI’s!

The project is realized through the Mobius Fellowship program of the Finnish Cultural Institute New York (and with the collaboration of Ilari Laamanen).

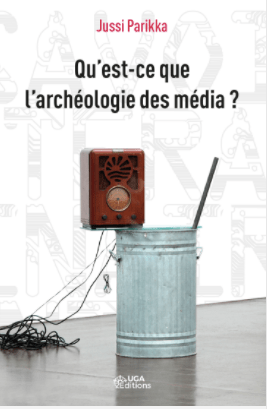

Qu’est-ce que l’archéologie des média?

The French translation of What is Media Archaeology? is now out. Titled Qu’est-ce que l’archéologie des média? it is translated by Christophe Degoutin and also includes a new preface by Emmanuel Guez from the PAMAL (media archaeology lab) in Avignon.

cover image from Haroon Mirza’s installation.

In his introduction to this book in the context of contemporary media theory, Guez nicely picks up on how my interest is not in building systems nor in ontological definition that nails down media archaeology for good. Instead, the book is a cartography of theoretical and methodological potentials, of paths taken and potentials for development, of necessary cross-fertilization and being aware of the blindspots. Hence this cartography (picking on Deleuze’s writing on Foucault and Rosi Braidotti’s apt ideas) is interested in positions, effects, operations and how media archaeology is exercised – a topic that I have been wanting to engage more recently through the current collaborative work on media (archaeology) labs as places of situated and institutional practice. And in the French context, it surely will resonate with a different set of theoretical heritage, current practices and media discourses than in some other contexts.

Apt timing, the French translation of Friedrich Kittler’s Gramophone, Film and Typewriter is the same month of January 2018 as well.

For more information and to order the book, see the publisher’s website.

For a recent interview in French, see “Zombies, virus et pollution : comment l’archéologie des médias imagine notre futur.”

For an earlier French translation of the conversation between me and Garnet Hertz on media archaeology, see “Archéologie des media et arts médiaux.“

Inventing Pasts and Futures: Speculative Design and Media Archaeology

I wrote a paper some years ago on media archaeology (esp. imaginary media research) and speculative design, to put the two parallel fields in closer dialogue. The text will be featured in a book that is still in preparation and because the first version was written some three-four years ago, I thought at least to add a couple of the first lines online. This is still the version that is not copy edited, but hopefully out one day too! Here’s the start. For the full draft version, please get in touch.

Inventing Pasts and Futures: Speculative Design and Media Archaeology

- Introduction: Imaginary Media as Impossible Yet Necessary Techniques

To be able to start with the non-existent, sometimes even the absurd, is a skill in itself. It can be a methodological way of approaching reality not as ready and finished but produced and open to further variations, potential and a temporality that includes the possibility of something else. Like with all methods, the skill of thinking the non-existent needs practicing. It also needs institutional contexts that are able to support such an odd task that seems devoid of actual truth value and easily dismissed as not incorporating the epistemological seriousness required of the academic subjects. Despite the difficulty of giving a good one-liner definition that could cover all aspects of different traditions of media archaeology, it is safe to say that it has been able to create an identity as a field interested in the speculative. This has meant many things from mobilisation of media history executed by way of surprising connections across art, design, technology and architecture to acknowledging the unacknowledged, a sort of a search and rescue-operation for devices, stories, narratives, uses and misuses left out of the earlier registry. Archaeology has been sometimes used as a general term for the way in which we investigate the conditions of existence of media culture, and the media technical conditions of existence of cultural practices – two things that are closely connected, with the two aspects in co-determining relations: media technology and cultural practices. And it also bends our notions of history and time itself. As Thomas Elsaesser (2016, p. 201) puts it, it is a symptom of a very different sort of a relation to the past: ‘on the one hand, it suggests a freeing up of historical inevitability in favour of a database logic, and on the other hand, it turns the past into a self-service counter for all manner of appropriations.’

Already, early on, imaginary media was one part of the media archaeological body of research. It had the clear aim of reminding scholars and artists that media technological reality was not to be restricted to what actually is. It was not to be contained by the histories of technological achievement but meant to relate to the broader cultural and artistic history, which technology can be imagined, and where it returns as imaginary attachments to values, affects, aspirations and dreams. Eric Kluitenberg (2011) articulates that such shifts are sometimes almost as if seamless, something rather prescient in the marketing discourses of digital culture. We feel constantly even emotionally attached to dream devices of corporations, carefully framed by their sales pitches as part of a wider infrastructure of desire. While such an attachment is odd enough, broadly speaking the discourses of imaginary connections constitute also our cultural topoi (Huhtamo 2011a), which then become the environment for recursive dreaming that characterizes consumer culture and production of reality.

But how boring it would be to restrict oneself to what is actual. A variantology of imaginary media, as Kluitenberg puts it (2011, p. 57) can reach out to theological discourses, aliens and the dead, to things untrue and yet so impactful for any account of cultural history. Such imaginations are ways to rethink the usual coordinates of time and space – the time of not merely a past-that-was, but a past-that-could-have been; a future imagined as one recurring fantasy of rejigging the time we are in now. These are the places that are not only distant but sometimes impossible. How liberating this feels instead of buying into the ready-made dreams. No wonder such strategies can be connected to a wider political imaginary that includes geographical, racialized and gendered others. Artists such as Zoe Beloff have set scenes for alternative media histories through the silent mediums themselves – female protagonists, written into the stories. Kluitenberg points to afrofuturism as one particularly interesting political imaginary. Indeed, as the director John Akomfrah puts it in an interview with Kluitenberg, afrofuturism and other imaginary media practices are not mere mental refuge. They produce and sustain new cultural practices and spaces in which black science fiction carves its own collective existence but also facilitates relations with, for example, gay and women’s movement including in the science fiction of Octavia Butler and Samuel Delaney. What is being approached is a black techno-cultural imagination where also music plays a key role in how pasts, presents, and futures co-determine each other in new ways: ‘Black science-fiction culture, especially music, figures the past in the present by matching the quest for ‘outer’ space with new journals into the inner “technological tape” space of black sound itself via the digital utopias of jungle and techno.’ (Kluitenberg and Akomfrah 2006, p. 293). Even if also imaginary media is at times defined as ‘untimely’ (Zielinski 2006, p. 30; Kluitenberg 2011, p. 56-57), it remains actually an interesting situated practice that is aware of geographies and can challenge the Eurocentric focus of some of the speculative design discourse and practice. Hence, the more interesting of such fabulations actually become ways to imagined situated critiques by way of imaginary. In some recent work, afrofuturism has also been connected to issues of cultural heritage as a project between speculative futures and records of the past (see Nowviskie 2016).

So what does it mean to think of media archaeological and imaginary media projects in the context of speculative design? The question itself acts as a conceptual probe that searches for specific practices in both media and design. Furthermore, it is also a probe that scans the disciplinary relations of two sets of discourses about the past and the future. As two parallel fields with not much contact in the past, speculative design and imaginary media research are interested in how alternative worlds might be created and how temporal, social, and technological fabulations situate coordinates of past-future in alternative ways. I will discuss different art and design projects, cross-fertilising the two traditions of media and design theory and practice, and aim to elaborate ways how media archaeology could contribute to speculative design and to some contemporary issues in critical design. There are some earlier ideas that have suggested how this might work. For example Bruce Sterling’s idea of ‘paleo-futures’ as ‘the reserve of historical ideas, visions and projections of the future—a historical futurity of that prospective’ (Hales 2013, p. 7) is one example of the shared suitably complex time-scales of overlapping design and media archaeological imaginations, but this chapter teases out further contexts for such reserves of historical ideas.

Image may contain

Visual culture nowadays.