>Art and Electronic Media

>

I wrote a review of Edward Shanken’s huge Art and Electronic Media just recently for the Finnish journal of audiovisual culture, Lähikuva. Well, the review is not out yet, and even when it will be, it’s of course in Finnish, so just a short summary. Any book that due to its size could be a proper murder weapon merits a word or two.

>Of Sheep and Women — from the Utrecht Feminist Research Conference

>

My attendance at the 7th Feminist Research conference in Utrecht will remain brief, but today’s two early keynotes were already enough to keep me happy. Instead of hazy “ideas in progress”, remediation of what the person did 20 years ago (and still doing) or unprepared ramble through of bullet points, we actually had two really nice presentations with good commentators after that.

What surprised me was that I actually liked Sara Ahmed’s paper, as she comes from a bit different direction to cultural analysis as I do. Her talk on “Killing Joy” focused on the notion of happiness — and feminism as a force of producing unhappiness, disruptions to expectations whether in dinner conversations or as a social cultural critical force. Despite the assumed natural goodness of happiness, we know little about what it is – this ontological question has always eluded philosophers as well with Kant already voicing critique of this notion: everybody wants happiness, but still we really don’t know much about what we want or will. Ahmed also pointed towards Betty Friedan’s early critique of the figure of “happy housewife”, and proceeded through a cartography of not only “archives of unhappiness” but contemporary field of knowledge production and feminism’s role in that.

So if the feminist is the kill joy at a coffee table, what does it mean more concretely as a horizon for production of knowledge? Ahmed was able to open up the concept’s etymology through its stem word “hap” – as in accidental, which pointed towards its role as something that happens to us, without control. Yet, it seems, especially in the midst of contemporary cultures of

standardized happiness production, there is much more to the notion than the early stems. In an interesting manner, Ahmed went through Nietzsche’s critique of habit and pointed out how its often more of a feeling of a feeling that an encounter of an object/event that causes happiness — or unhappiness. Such things are often so loaded that we feel them before they happen in a manner of anticipatory causality – and odd futurity of sorts, that as a notion sounds very Deleuzian and points towards some of the themes Brian Massumi is known of. Again, outside her presentation, I was left thinking of happiness as an order-word of sorts that organizes emotions and feelings, as well as affects outside the linguistic sphere into such patterns of expectation that can be packaged also for the consumer industry.

The critical point of her presentation followed from the fact that things are not always causing what they should. The pattern of dissonance amidst things/events/discourses that should be consumed as expected is what can trigger points of critique – affect aliens/alien affects. Ahmed’s notion of affect differs quite a lot I think from that of e.g. Massumi, but the point here is clear, and Ahmed did use quite a lot of examples that pointed towards the pre-linguistic and even the pre-individual. This is why I was a bit disappointed with her conclusions that were framed through the discourse of false consciousness: breaking out of habits and modes of discourse as a tactic of feminism/feminists is something known from everyday life to academic articles, but Ahmed’s examples could have pointed towards the spheres of non-conscious cognition as well – its role in the cultures of happiness and expectation, the strange futurities that guide the present.

The second speaker Claire Colebrook delivered quite well what I expected; solid Deleuzian viewpoints, although not really hammering home her own point. This is something I at times have noted with Milla of her articles too; excellent positioning of questions and agendas, but a stronger development of her own solution to the positions would be needed. Today Colebrook talked about the notion of vitalism, and started by dividing them into three:

1) Cartesian: vitalism of mind, that contrasts with matter (CC pointed well, how Descartes is almost a straw-man for much of later criticism, which neglect the fact that Descartes also was quite radical in his time, and raised a huge row among the Christians).

2) The vitalism we find in theories of emergence, a more contemporary notion. This is what recent theories of cognition among others have embraced from Damasio to Dennett and others. A new appreciation of dynamics and “being-in-the world” which has led to the discovery of e.g. Heidegger by brain scientists. Interestingly, a lot of them talk about the world as “meaningful”. Organism emerges from complex dynamics, and hence no duality of mind and matter. Yet, organism-centred.

3) A perverse nomadic vitalism of Braidottian sorts which is not a vitalism of the organism/organic, but a much more distributed way of questioning what even counts as “a body”, “a life”.

To put it shortly, Colebrook pointed out how feminism has always been ecofeminism of sorts (which, I may add as a footnote, is a point elaborated by Verena Andermatt Conley in her study Ecopolitics). It has always attended to notions of relationality, milieu and crossing of the boundary between self and others, but still we need to make a clear case how it does not mean a simple “care for the environment” – in her critique of the notion of environment, Colebrook claims that it still relies too much on the idea of the Human Agent as separated, only surrounded by nature, instead of the idea of milieu that is something that transversally cuts through the human and her outside (an idea stemming e.g. from Simondon that Colebrook did not mention.)

Whereas the ideas on environing “caring” notions of being in the world have spread in the sciences as well as management studies (as Colebrook dryly noted, it’s the middle-managers who are now anti-Cartesian), we need to develop much more radical and less organism centred notions of vitalism. The organic model, even if reliant on dynamics and emergence, still thinks too much of the human being as the key agent for example in terms of the crises circulating around (eco and financial), instead of a more radical opening by nomadic vitalism that starts with the questions: what counts as a life, what counts as a body, what is even worth saving, and preserving? We need to keep an eye on the inhuman temporalities in which such notions of vitalism, the body etc. are to be interrogated also because of the practical consequences in the midst of ecocrisis and the financial crisis. I like Colebrook points a lot, but a key question/comment rose to mind: I think the division between the good nomadic vitalism and the still bad emergent vitalisms is not that clear-cut even if she has a point re. organisms. This still needs more work, and was implicitly raised by Rosi Braidotti in her comment to Colebrook’s talk: how the sciences can feed into and destabilize notions within cultural analysis.

Braidotti was again her usual vital self, with an amazing charisma and charm in the way she both offered a lucid philosophical point but also political empowerment that was gender-specific but as much tending the crucial points about geopolitics.

Braidotti pointed towards the key axiomatics of the modern world (and philosophy!) and hence cultural studies in terms of “otherness” – and the relays through which otherness has been negotiated: sex, race, nature; also axes of theory as we know after some decades of

representational analysis and intersectionality. Yet, the point about vitalism is made concrete as a challenge when we realize how such Master Codes have been reshuffled and scrambled by developments in the biosciences, -technologies, cognitive sciences, etc. which very concretely force us to rethink what are the differences that articulate otherness. In her powerful and funny punch line, Braidotti said that if her generation was focused on Dolly Parton, for the younger one its Dolly the Sheep. In her sweep from the demand for a “philosophy with an accent”, or in the diasporic mode (a point that I as a non-native English speaker loved!) to the implications of sexual perversions and sexuality as a force to create novelties, Braidotti was unbeatable, again. Both Braidotti and Colebrook agreed of course of the need to develop such thought that does not stem from the organism, but develops new forms of imagining; polymorphic sexualities, novelties of the mind and the body, new accents that destabilize the master codes.

Tetris: The Training Ground

>

I am for sure not the only one wishing Tetris a happy 25 year old birthday, but still, the game has deserved it. Its addicting, fun, and indeed: with no purpose in itself. Sounds familiar? Almost like everyday life, except the fun bit.

That’s actually what I quite often find lacking in some of the even brilliant Italian and Italian inspired writers of post-Fordism: a meticulous and accurate analysis of the network and computer society that contributes and frames those themes that Virno, Lazzarato, Negri, Hardt, etc. are offering. I know Bifo gets closer to this topic, but I feel that on this front, there is a huge amount to be done.

>Cultures of Creativity With No Talent: Cola-Olli

>As usual, I missed something that most of the country is following, this time Britain’s Got Talent. I was not too bothered about who Susan Boyle is, or the various “talented” Brits featured on the show such as the Stavros Flatley, even if, only too late, I started thinking about this in the context of the banality of talent shows more generally. How do such talent shows relate to the hype on “creative cultures”?

>Genitals in the Field of Vision

>If you happened to see an unusual amount of genitals a couple of days ago, you might have stumbled across Youtube’s “Porn Day” — a prankster or a media activist coup that was meant to raise awareness of the new music video policies on Youtube. So if you were looking for Hannah Montana or Jonas Brothers, you might have found something totally different, to put it bluntly. Responsibility was claimed by a Japanese message board community, but we could extend the logic a bit further.

>Butler in Cambridge

>Just back from Judith Butler’s talk that was part of a symposium in honor of Juliet Mitchell’s retirement. First of all, I am not sure whether to be amused or angry of the “theme music” to the session which was Vivaldi’s music softly escorting the audience into what you would not expect to be one focusing on socialist feminism…but then again, that was Cambridge University, and indeed that is one way to just innocently remind the audience of the Prestige and Tradition of the place. I somehow wonder how any seminar so conscious of the roles of cultural practices in creating solidified and stratified notions of culture and relationships can tolerate such an “intro.”?

Office-Divaesque

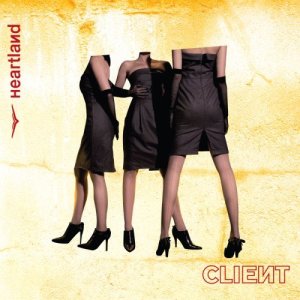

In order to keep sane in the midst of marking, I want to write a post that I have been thinking for a while. Now that I have been banned of going on about Lily Allen as the softcore consumerist critique on the footsteps of Ballard (don’t ask), I have focused my energy on another new personal discovery: Client. Well, again, I noticed I am somewhat several years late, so that something new to me has been around for a long time.

Client mixes through its music and visuals a touch of Kraftwerk with Depeche Mode, but in a manner that I would describe as creating a mesmerizing feel of detached, cold, minimalist erotics. Hence, the adoption of themes that all refer to the key modern institutional language of corporations, admin and offices is an ingenious one and amounts to creating an image of the lead singer, Client B, as the Office Diva.

The repetitious catchy music is emblematic of such urban spaces in a similar manner as Kraftwerk tapped into the technological fantasies of modernity on the brink of post-fordist culture. The influences are clear as well. A certain flirtation with Germany; with songs such as Köln; and Drive (ref. Autobahn). The highly rationalized urban spaces and organizational grids of driving culture are opened up to afford also lines of flight as when Client B sings “White lines on a motorway/I’m alive/I’m alive”.

Direct references to erotics are continuously present but again on the fine border between passionate and cool, detached, as their uniforms promise. Its the style of erotics that stems from Xerox Machines:

“Let’s get together before it’s too late/ Collect up the ideas and duplicate/ Filling in the forms/ send ‘em off tonight/ And you’ll be the owner/ of the copyright/ Of the copyright, of the copyright.”

Desire is machinic, and machines can be the object and relay of desire; this is a key modern theme that actually is the cultural historical background for the fetishistic desire for technology. Cool, detached, uniform; the fetish par excellence. Yet, the gender aspect is not neglected, and the male fantasy where machines/women are conflated is exposed: “You said you want to set my soul free/but I’m just an object of your fantasy.” (“Lights go out”). The banal cultural theoretical observation gains its true strength from the ritornello, the returning rhythmic elements of urban alienation.The true gem from a media theorists position is of course Radio.

The post-punk alienation is strengthened by the banality of “radio” as the thematic tie between the bored-oh-so-bored singing voice and the externalized world glassed out through the television screen and voiced out through radio “news”. (“They call it news/its not to me/The world’s a mess/ on my TV”). Again, the banality of the lines is only understood through the middle-classed-office-divaesque mannerism and voice of Client B. The broadcast media of the modern age is also the relay for the private (but hence so easily approachable in the age of mass reproduction) angst of Client. Customizing Adorno?

I have been thinking — mostly as a joke — a new research project on “Admin Culture”; if that would ever actualize in any way, I would definitely include Client there, and offer a much more insightful approach to their sonic art.

>New Materialism, a-signification

>As the publisher is slow — metaphysically slow, of cosmic proportions — getting out our Spam Book, I spend time reading others book. As if I would not otherwise. Well, after finishing Shaviro’s excellent book of Whitehead that convinced me that I need to rethink my ideas re. ethologies of software from a Whiteheadian perspective, I reserved a bit of time for Gary Genosko’s Félix Guattari – A Critical Introduction. Not able here to give a full-fledged review of the book, I just want to point towards the themes that I found really useful.