Algorithms for the everyday life

11 steps for the superior handwash, and to achieve safety (step 11) for you and the ones close to you.

Affect, software, net art (or what can a digital body of code do-redux)

After visiting the Manchester University hosted Affective Fabrics of Digital Cultures-conference I thought for a fleeting second to have discovered affects; its the headache that you get from too much wine, and the ensuing emotional states inside you trying to gather your thoughts. I discovered soon that this is a very reductive account, of course — and in a true Deleuzian spirit was not ready to reduce affect into such emotional responses. Although, to be fair, hangover is a true state of affect – far from emotion — in its uncontrollability, deep embodiment.

What the conference did offer in addition to good social fun was a range of presentations on the topic that is defined in so many differing ways; whether in terms of conflation it with “emotions” and “feelings”, or then trying to carve out the level of affect as a pre-conscious one; from a wide range of topics on affective labour (Melissa Gregg did a keynote on white collar work) to aesthetic capitalism (Patricia Clough for example) which in a more Deleuzian spirit insisted on the non-representational. (If the occasional, affective reader is interested in a short but well summarizing account of differing notions of affect to guide his/her feelings about the topic, have a look at Andrew Murphie’s fine blog posting here – good theory topped up with a cute kitty.)

My take was to emphasise the non-organic affects inherent in technology — more specifically software, which I read through a Spinozian-Uexkullian lense as a forcefield of relationality. Drawing on for example Casey Alt’s forthcoming chapter in Media Archaeologies (coming out later this year/early next year), I concluded with object-oriented programming as a good example of how affects can be read to be part of software as well so that the technical specificity of our software embedded culture reaches out to other levels. Affects are not states of things, but the modes in which things reach out to each other — and are defined by those reachings out, i.e. relations. I was specifically amused that I could throw in a one-liner of “not really being interested in humans anyway” — even better would have been “I don’t get humans or emotions”, but I shall leave that for another public talk. “I don’t do emotions” is another of my favourite one’s, that will end up on either a t-shirt or an academic paper.

The presentation was a modified version from a chapter that is just out in Simon O’Sullivan and Stephen Zepke’s Deleuze and Contemporary Art-book even if in that chapter, the focus is more on net and software art. I am going to give the same paper in the Amsterdam Deleuze-conference, but as a teaser to the actual written chapter, here is the beginning of that text from the book…

1. Art of the Imperceptible

In a Deleuze-Guattarian sense, we can appreciate the idea of software art as the art of the imperceptible. Instead of representational visual identities, a politics of the art of the imperceptible can be elaborated in terms of affects, sensations, relations and forces (see Grosz). Such notions are primarily non-human and exceed the modes of organisation and recognition of the human being, whilst addressing themselves to the element of becoming within the latter. Such notions, which involve both the incorporeal (the ephemeral nature of the event as a temporal unfolding instead of a stable spatial identity) and the material (as an intensive differentiation that stems from the virtual principle of creativity of matter), incorporate ‘the imperceptible’ as a futurity that escapes recognition. In terms of software, this reference to non-human forces and to imperceptibility is relevant on at least two levels. Software is not (solely) visual and representational, but works through a logic of translation. But what is translated (or transposed) is not content, but intensities, information that individuates and in-forms agency; software is a translation between the (potentially) visual interface, the source code and the machinic processes at the core of any computer. Secondly, software art is often not even recognized as ‘art’ but is defined more by the difficulty of pinning it down as a social and cultural practice. To put it bluntly, quite often what could be called software art is reduced to processes such as sabotage, illegal software actions, crime or pure vandalism. It is instructive in this respect that in the archives of the Runme.org software art repository the categories contain less references to traditional terms of aesthetics than to ‘appropriation and plagiarism’, ‘dysfunctionality’, ‘illicit software’ and ‘denial of service’, for example. One subcategory, ‘obfuscation’, seems to sum up many of the wider implications of software art as resisting identification.[i]

However, this variety of terms doesn’t stem from a merely deconstructionist desire to unravel the political logic of software expression, or from the archivists nightmare á la Foucault/Borges, but from a poetics of potentiality, as Matthew Fuller (2003: 61) has called it. This is evident in projects like the I/O/D Webstalker browser and other software art projects. Such a summoning of potentiality refers to the way experimental software is a creation of the world in an ontogenetic sense. Art becomes ‘not-just-art’ in its wild (but rigorously methodological) dispersal across a whole media-ecology. Indeed, it partly gathers its strength from the imperceptibility so crucial for a post-representational logic of resistance. As writers such as Florian Cramer and Inke Arns have noted, software art can be seen as a tactical move through which to highlight political contexts, or subtexts, of ‘seemingly neutral technical commands.’ (Arns, 3)

Arns’ text highlights the politics of software and its experimental and non-pragmatic nature, and resonates with what I outline here. Nevertheless, I want to transport these art practices into another philosophical context, more closely tuned with Deleuze, and others able to contribute to thinking the intensive relations and dimensions of technology such as Simondon, Spinoza and von Uexküll. To this end I will contextualise some Deleuzian notions in the practices and projects of software and net art through thinking code not only as the stratification of reality and of its molecular tendencies but as an ethological experimentation with the order-words that execute and command.

The Google-Will-Eat-Itself project (released 2005) is exemplary of such creative dimensions of software art. Authored by Ubermorgen.com (featuring Alessandro Ludovico vs. Paolo Cirio), the project is a parasitic tapping in to the logic of Google and especially its Adsense program. By setting up spoof Adsense-accounts the project is able to collect micropayments from the Google corporation and use that money to buy Google shares – a cannibalistic eating of Google by itself. At the time of writing, the project estimated that it will take 202 345 117 years until GWEI fully owns Google. The project works as a bizarre intervention into the logic of software advertisements and the new media economy. It resides somewhere on the border of sabotage and illegal action – or what Google in their letter to the artists called ‘invalid clicks.’ Imperceptibility is the general requirement for the success of the project as it tries to use the software and business logic of the corporation through piggy-backing on the latter’s modus operandi.

What is interesting here is that in addition to being a tactic in some software art projects, the culture of software in current network society can be characterised by a logic of imperceptibility. Although this logic has been cynically described as ‘what you don’t see is what you get’, it is an important characteristic identified by writers such as Friedrich Kittler. Code is imperceptible in the phenomenological sense of evading the human sensorium, but also in the political and economic sense of being guarded against the end user (even though this has been changing with the move towards more supposedly open systems). Large and pervasive software systems like Google are imperceptible in their code but also in the complexity of the relations it establishes (and what GWEI aims to tap into). Furthermore, as the logic of identification becomes a more pervasive strategy contributing to this diagram of control, imperceptibility can be seen as one crucial mode of experimental and tactical projects. Indeed, resistance works immanently to the diagram of power and instead of refusing its strategies, it adopts them as part of its tactics. Here, the imperceptibility of artistic projects can be seen resonating with the micropolitical mode of disappearance and what Galloway and Thacker call ‘tactics of non-existence’ (135-136). Not being identified as a stable object or an institutional practice is one way of creating vacuoles of non-communication though a camouflage of sorts. Escaping detection and surveillance becomes the necessary prerequisite for various guerrilla-like actions that stay ‘off the radar.’

Bookmachines, Soundmachines

Kettle’s Yard had today a CoDEful of people performing on “Musical and Poetic Approaches to Technology, from subversive, DIY and historical perspectives.” By CoDEful I mean Katy Price, Tom Hall and Richard Hoadley, all affiliated with our institute.

The experimental takes on sound, music and performance moved from digital investigations into soundscapes (Katherine Norman’s pieces) to for example physical computing and interface experiments as with Richard Hoadley who performed with his self designed Gaggle too — along with two new devices, Wired and Gagglina.

I truly enjoyed Katy Price’s performance piece Bookmachine which is described as “found poem drawn from three sources about books and machines.” The opening line “the book is a machine to think with” is a declaration of book’s haptic, sonic, material qualities; an exploration into the pragmatics of the book. (And as I learned, comes from I.A.Richard’s). Indeed, the book is touched, scraped, made into a sonic platform; it is torn, taped back together, punctured. The book is less read, and when its read, its not a work of extracting meanings from it, for sure. The book is “typed into a BBC Microcomputer simulator running ‘Speech’ and the speech facility in a Macbook.” The book does, and is an object of doing much more than meaning in a Deleuzian spirit.

This is where I am alluding to, Deleuze and Guattari on the book: the root-book is very different even if its the classical form of the book; hierarchical and full of meaning. We read such books as we should read books — the way we are taught. Start in the beginning, think of what it means. The modernists then were already cutting up books (cut-ups by Burroughs) and making new kinds of series proliferate. But books can be made to do other kinds of things; books are machines, and machines connect. They connect to senses, new uses, making books into objects, trajectories, surfaces, scapes. A machine to think with alludes to the fact that books always function as part of assemblages. We like to think of book’s as organic and self-sustaining, but they always are there to help to do stuff, to think with, to accompany. We become with books. And if the book is a machine to think with, it also alludes that there are other machines to think with too; that the book is a machine similarly as computers and such are.

Book as a machinic assemblage is much more than we usually attribute to literature, and sees it even as a , well, war-machine (in the DeleuzeGuattarian-sense again). To quote Gregg Lambert:

“…literature functions as a war machine. ‘The only way to defend language is to attack it'(Proust, quoted in CC4). This could be the principle of much of modern literature and capture the sense of process that aims beyond the limit of language. As noted above, however, this limit beyond which the outside of language appears is not outside language, but appears in its points of rupture, in the gaps, or tears, in the interstices between words, or between one word and the next.” (Lambert, The Non-Philosophy of Deleuze, 141).

Literally, what lies between words are blank gaps on the page, but also paper, and the porous surface of inscription. There is always a lot that goes on between any word – much more than hallucination of meaning. The stuttering “and” is what constitutes an experimental assemblage of the book machine which tries out the various material modalities in which text, covers, paper, expose much more than meaning. The rhizome-book is the bookmachine, it reaches to outsides and neglects illusions of books as images of the world. It represents less, but sounds a lot more.

The book too has its on level of “body without organs” — the final phrase from the performance. Much more, such perspectives relate to futures of literature and literature studies. New territories of how we approach literature, books, meanings do not take at face value the idea of hermeneutics and deciphering meanings in that traditional sense, but are open to, well, opening up the book in different ways. Literature can be made into such new contexts of use and imagination where semantics and interpretation can be seen as only one way of “practicing literature”. This is where the translation of literature whether into data open to algorithmic manipulations, or then new realms of sensation in terms of multimodality, or part of other creative, experimental takes finds its futures.

Across scales, contagious movement

I wrote this short text as a response, inspired by Stamatia Portanova’s recent introduction to her concept of movement-object…published on the In Medias Res-website.

Why is global capitalism so interested in dance? Why is it so interested in flexible, able, creative bodies that show virtuosity and skill? It seems that the emblematic body of contemporary network(ed) capitalism of creative industries and digital economy is that of the dancer, the performer, what Virno referred to as virtuosity; not solely the individual performer however, but indeed a collective quite often. Its flash mobs on train stations, not the worker at the conveyer belt; indeed, train stations instead of factories. What is being produced is movement, or perhaps, from a moving, creative, related set of bodies something emerges; what is that what interests capitalism in that sense? Of course, football is the great art of relationality (think of Douglas Gordon’s Zidane-film!) but as much a condensation of creative capitalism; a condensation of not only flows of skill, but flows of capital and profit. In South-Africa, at the moment, with the World Cup approaching, new territories of security are being created where wrong bodies (street kids, and other not-wanted-disturbances) are being cleaned out from the streets in preparation for the celebration of global society under the banner of football.

An excerpt from another text, forthcoming:

“Indeed, the dancing and moving body can be seen in historical terms as a specific form of knowledge production with an increasing economic importance. Dance is the perfect interface for cultural theories of movement (bodies in variation) to understand the complexity of interaction, an ethology of forces/bodies and the object of cultural industries of affect and experiences. Nigel Thrift writes: ‘[…] dance can sensitize us to the bodily sensorium of a culture, to touch, force, tension, weight, shape, tempo, phrasing, intervalation, even coalescence, to the serial mimesis of not quite a copy through which we are reconstituted moment by moment’ (2008: 140).”

“Not quite a copy” seems to be the contagious element of propagation.

You (referring to Stamatia) start with viruses, with bacteria, which is apt in terms of thinking the contagious nature of gesturality/movement (despite a post-fordist emphasis on flexible bodies, actually the mapping of the gestural, flexible body was part of the earlier phase of capitalism, the cinematic one already since he 19th century) and movement-objects as you call them. It seems to convey the idea of such objects themselves as condensations of intensities that can spread across levels, in this case from the thickness of the event/bodies performing in relation to e.g. algorithmic environments, digital techniques/milieus of creation. Indeed, its not only an abstraction of lived relations of organic kinds, but another scale of relations that is being superposed, or ties in with bodies, and that intertwining of scales and techniques interests me a lot. The digital object is far from static but incorporates too an intensity that stems from its relational status. We can also approach digital objects through the notion of affect whether on the level of design where e.g. object-orientated-design deals with such relations, or then more widely through the assemblage nature of digital nature. Digital objects, software and such, are, for me, characterised by their translational capacities. Not only that through algorithmic measures we are able to abstract etc. things into datasets, but that such abstractions return to organic bodies and their actions; they return as sounds and visions, as actions or frameworks for action (operating systems, bank cash dispensers, and such). This generative circuit that software participates in between a variety of bodies, this relationality, is how I would read also “movement-objects” circulating and distributing certain relations and gesturality even.

I think this multiplicity of ecologies is one thing that strikes me about your movement-objects; they always creatively “mediate” between scales; whether digital objects-organics, or then the idea about beats, where the beat-object is formed through combination of grains, as you put it following Alanna, and where on another scale of bodies’ beats create combinations; bodies pulsating together at a disco! Or again, at the train station as with flash mobs harnessed as part of mobile operator adverts! Its contagious, indeed, and again ties in these contemporary themes together with crowds, social imitation as creativity of bodies in concert, all symptomatic of modernity already in the sense Gabriel Tarde talked about (and more recently Tony Sampson has been interested in!).

New Materialisms and Digital Culture -symposium

Please find below information and registration possibility for our symposium

Please find below information and registration possibility for our symposium

on new materialist cultural analysis as well as info for the launch event of the

CoDE institute and the affiliated Digital Performance Laboratory.

An International Symposium on Contemporary Arts, Media and Cultural Theory

Date: Monday 21 June 2010

Time: 10:00 – 17.30 (18.00 Performance and CoDE Launch)

Venue: Hel 201, Anglia Ruskin University, East Road, Cambridge

Far from being immaterial, digital culture consists of heterogeneous bodies, relations, intensities, movements, and modes of emergence manifested in various contexts of the arts and sciences.

This event suggests “new materialism” as a speculative concept with which to rethink materiality across diverse cultural-theoretical fields of inquiry with a particular reference to digitality in/as culture: art and media studies, social and political theorising, feminist analysis, and science and technology studies.

More specifically, the event maps ways in which the questions of process, positive difference or the new, relation, and the pervasively aesthetic character of our emergences with the world have lately been taken up in cultural theory. It will engage explorations of digital culture within which matter, the body and the social, and the long-standing theoretical dominance of symbolic mediation (or the despotism of the signifier) are currently being radically reconsidered and reconceptualised.

The talks of the event will probe media arts of digital culture, sonic environments, cinematic contexts, wireless communication, philosophy of science and a variety of further topics in order to develop a new vocabulary for understanding digital culture as a material culture.

Speakers include: Dr David M. Berry, Dr Rick Dolphijn, Dr Satinder Gill, Dr Adrian Mackenzie, Dr Stamatia Portanova, Dr Anna Powell, Dr Iris van der Tuin and Dr Eleni Ikoniadou.

The academic programme will be followed by a physical computing and dance performance involving CoDE affiliated staff (Richard Hoadley and Tom Hall) along with choreographers Jane Turner, Cheryl Frances-Hoad and their dancers.

Following the symposium there will also be a short workshop for PhD students on Tuesday 22 June led by Van der Tuin and Dolphijn along with Milla Tiainen and Jussi Parikka. The aim of the workshop is to enable students to discuss and present brief intros to their work on the theme of new materialist analysis of culture and the arts with tutoring from the workshop leaders. The workshop is restricted to max. 10 students. Participation for the selected ten is include in the registration fee. If you are interested, please send an informal message to either milla.tiainen@anglia.ac.uk or Jussi.parikka@anglia.ac.uk along with a short (approx. 1 page) description of your PhD work and its relation to new materialism.

In addition, we are planning an informal introductory workshop for Tuesday afternoon on experimental performance and physical computing.

The event is sponsored by CoDE: the Cultures of the Digital Economy research institute and the Department of English, Communication, Film and Media at Anglia Ruskin University.

Please register your place here

Fee: £20

Programme

Anglia Ruskin University. East Road, Cambridge, UK, Helmore Building, room Hel 201

June 21, Monday

10.00 Welcome and what is new materialism, Milla Tiainen and Jussi Parikka

10.15 Anna Powell (Manchester Met): Electronic Automatism: Video Affects and The Time Image

11.10 Break

11.30 Iris van der Tuin (Utrecht): A Different Starting Point, a Different Metaphysics”: Reading Bergson and Barad Diffractively

Rick Dolphijn (Utrecht): The Intense Exterior of Another Geometry

12.30 Lunch

13.45 Stamatia Portanova (Birkbeck): The materiality of the abstract (or how movement-objects ‘thrill’ the world)

Eleni Ikoniadou: Transversal digitality and the relational dynamics of a new materialism

Satinder Gill (Anglia Ruskin/CoDE and Cambridge University): “Rhythms and sense-making in responsive dense-space’

15.20 break

15.40 David Berry: Software Avidities: Latour and the Materialities of Code.

16.10 Adrian Mackenzie (Lancaster) Believing in and desiring data: R as ‘ next big thing

17.00 closing and a break

18.00 Open launch and drinks event for the Digital Performance laboratory (CoDE, Music and Performing Arts, Anglia Ruskin) and a science-arts interdisciplinary performance Triggered. Recital-hall, Helmore Building (029), East Road, Anglia Ruskin, Cambridge.

‘Triggered’ showcases the results of a practice-as-research project into methods of interdisciplinary collaboration between a group of contemporary dancers, musicians and music technologists. The nature of this collaboration has allowed performance to emerge from artists and disciplines interacting and responding to each other. The bespoke technologies used in the project enable sophisticated dialogue between movement and sound, between music composition and choreography. The nature of interaction and narratives created are key areas of investigation and these areas will explored in a workshop on the second day of the conference. Performing, choreographing, composing and building the production are Cheryl Frances-Hoad, Tom Hall, Richard Hoadley, Jane Turner & dance company.

Day 2 (June 22)

10.00-12.30 Helmore 251

New materialism: art, science, media –workshop with selected PhD students with Dr Iris van der Tuin and Rick Dolphijn, along with Milla Tiainen and Jussi Parikka

12.30-14.00 lunch

14.00 an experimental performance/HCI workshop and interaction possibility with Jane Turner, Cheryl Frances-Hoad, Dr Satinder Gill, Dr Richard Hoadley and Dr Tom Hall.

Polyverses

The easiest target to ease your pain in the midst of funding cuts and the crisis of British universities is to blame the post 1992 universities – the ex-polytechnics. It seems that in the still very rigidly divided British class society, its the ex-polytechnics that are responsible for all the bad in the academic cultures of the Empire. It seems that the good old values in hard sciences and English (which still quite recently, less than 100 years ago was seen as a Mickey Mouse subject as well, but now celebrated as a corner stone of UK universities) are being threatened by such transdisciplinary newcomers as media studies. Indeed, I would be afraid too, as what the future of universities will need are new mixed perspectives, hybrid disciplines that are able to smoothly maneuver between critical theory, technology and culture and develop an understanding of the nature-culture (i.e. science-humanities) continuum.

Hence, it is joyful to read in the midst of polytechnic-bashing about 19th-century — and British 19th-century specifically, when such institutions as the Royal Polytechnic Institution were not only celebrated back here but also envied across Europe. Such Polytechnics were indeed leading in various fields so crucial for the whole birth of technological, scientifically driven media culture that was emerging back then. Scientific progress, new forms of visualisation and spectacle, curiosities of useful and ephemeral kinds, were recognized to co-exist in a manner that indeed was a mix of popular attractions and scientific interest. As said, such polyverses were envied across Europe: “‘When will Paris have its own Polytechnic Institution?’ Abbé Moigno asked impatiently in his magazine Le Cosmos in August 1854″ (Mannoni, The Art of Light and Shadow, p 268). (Moigno was btw. anyway a big fan of Anglo-American sciences, and did translations and introductions to developments at the other side of the Channel). The French had been at the forefront of developing inventions concerning light and its manipulation in terms of various projection and other apparatuses, but it seems that around mid 19th-century, Britain was able to provide a strong institutional support for development of such inventions on a wider scale too.

What to me is curious about such institutions that engaged with not so much in high abstract science but in experimental, hands-on and engineering approaches to new ideas and innovations is how they are, actually, different from Royal Science. Indeed, in this case I am using Royal a bit differently and more in the fashion that the philosophers Deleuze and Guattari used the concept. For the two French philosophers, Royal Science is one connected to the State as a power formation, and aims at stabilized formations, predictabilities, abstracted forms of ideal and imperial kinds. Naturally such classic institutions as Royal Polytechnics and such were created closely with State interests (science and technology was seen already then as the flagship for the Empire, not only know in the midst of the Digital Economy hype), but perhaps there is a potential to see a nomadic undercurrent in some of the interests of knowledge/creation in them as well, that is relevant for a consideration of contemporary institutions. This is indeed where the other concept, an alternative from Deleuze and Guattari kicks in; nomadic science that is an intellectual/pragmatic war machine for them. It is less interested in discovering organic, ideal and fixed essences than mapping out matter in its intensity, full of singularities that can take that active matter into surprising directions.

Nomadic science experiments with matter on hand; it teases out potentials, and directions for becoming/use/applicability to use a bit different terms in a manner that does stay close to the dirtyness of the world. This is where practical, experimental sciences, engineering and “applied perspectives” can actually carve out more about the world in its intensive materiality, than the royal sciences. It is for me an artistic perspective to science/technology; the much talked about field of sci-arts that can work taking aboard “the best of both worlds”, so to speak. The cutting edge ideas in science and technology, but recontextualised in artistic methodologies and critical agendas. (And yes, not being only naive: I am completely aware how well embedded certain science-art collaborations are in economic wealth creation and even in military related developments and institutions).

Perhaps such perspectives have importance on various levels; to perspectives of media archaeology that are interested in nomadic ideas, practices and such assemblages of experimentation where invention happens in pragmatics. Not the inventions of for example media technologies in terms of their mathematics or logical implications, but in terms of experiments with materials, machines and such. A media archaeology of dirty machines, and trying out.

But it has importance also to ideas concerning contemporary institutions of knowledge/creation. Ex-polytechnics should perhaps more explicitly celebrate the engineering, arts, and applied sciences background, but not forgetting that theory is a practice too. This includes it as work of trying out, aberration, and dirty experimentation that works best in close proximity with the materiality of the world. Naturally its clear that there is a strong pull towards such Polyverses as the flagship of Royal interests; i.e. in various cases for example part of the new Digital Britain and the future of the Digital Economy. Yet, we should dig out minor passages, imperceptible places of research-creation and such where also new ideas, tinkering and experimentation without respect to theory-practice division can take place.

Security and Self-regulation in Software Visual Culture

“Not long ago it would have been an absolutely absurd action to purchase a television or acquire a computer software to intentionally disable its capabilities, whereas today’s media technology is marketed for what it does not contain and what it will not deliver.” The basic argument in Raiford Guins’ Edited Clean Version is so striking in its simplicity but aptness that my copy of the book is now filled with exclamation marks and other scribblings in the margins that shout how I loved it. At times dense but elegantly written, I am so tempted to say that this is the direction where media studies should be going if it did not sound a bit too grand (suitable for a blurb at the back cover perhaps!).

I shall not do a full-fledged review of the book but just flag that its an important study for anyone who wants to understand processes of censorship, surveillance and control. Guins starts from a theoretical set that contains Foucault’s governmentality, Kittler’s materialism and Deleuze’s notion of control, but breathes concrete specificity to the latter making it really a wonderful addition to media studies literature on contemporary culture. At times perhaps a bit repetitive, yet it delivers a strong sense of how power works through control which works through technological assemblages that organize time, spatiality and desire. For Guins, media is security (even if embedding Foucault’s writings on security would have been in this context spot on) — entertainment media is so infiltrated by the logic of blocking, filtering, sanitizing, cleaning and patching (all chapters in the book) that I might even have to rethink my own ideas of seeing media technologies as Spinozian bodies defined by what they can do…Although, in a Deleuzian fashion, control works through enabling. In this case, it enables choice (even if reducing freedom into a selection from pre-defined, preprogrammed articulations). Control is the highway on which you are free to drive as far, and to many places, but it still guides you to destinations. Control works through destinations, addresses — and incidentally, its addresses that structure for example Internet-“space”.

Guins’ demonstrates how it still is the family that is a focal point of media but through new techniques and technologies. Software is at the centre of this regime – software such as the V-Chip that helps parents to plan and govern their children’s TV-consumption. Guins writes: “The embedding of the V-Chip within television manifests a new visual protocol; it makes visible the positive effects of television that it enables: choice, self-regulation, interaction, safe images, and security.” What is exciting about this work is how it deals with such hugely important political themes and logics of control, but is able to do it so immanently with the technological platform he is talking about. Highly recommended, and thumbs up.

>Nick Cook talk on Beyond reference: Eclectic Method’s music for the eyes

>Another ArcDigital and CoDE talk coming up…

Professor Nicholas Cook, Cambridge University:

Beyond reference: Eclectic Method’s music for the eyes

Date: Tuesday, 11 May 2010

Time: 17:00 – 18:15

Location: Anglia Ruskin University, East Road, Cambridge, room Hel 252

Screen media genres from Fantasia (1940) to the music video of half a century later extended the boundaries of music by bringing moving images within the purview of musical organisation: the visuals of rap videos, for example, are in essence just another set of musical parameters, bringing their own connotations into play within the semantic mix in precisely the same way as do more traditional musical parameters. But in the last two decades digital technology has taken such musicalisation of the visible to a new level, with the development of integrated software tools for the editing and manipulation of sounds and images. In this paper I illustrate these developments through the work of the UK-born but US-based remix trio Eclectic Method, focussing in particular on the interaction between their multimedia compositional procedures and the complex chains of reference that result, in particular, from their film mashups.

Professor Nicholas Cook is currently Professor of Music at the University of Cambridge, where he is a Fellow of Darwin College. Previously, he was Professorial Research Fellow at Royal Holloway, University of London, where he directed the AHRC Research Centre for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music (CHARM). He has also taught at the University of Hong Kong, University of Sydney, and University of Southampton, where he served as Dean of Arts.

He is a former editor of the Journal of the Royal Musical Association and was elected a Fellow of the British Academy in 2001.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicholas_Cook

The talk is organized by the Cultures of the Digital Economy Institute at Anglia Ruskin University and the Anglia Research Centre in Digital Culture (ArcDigital).

The talk is free and open for all to attend.

>"Uncovering the insect logic that informs contemporary media technologies and the network society"

>

Here is the blurb that University of Minnesota Press are going to use for the catalog for their Fall 2010 books…mine is coming out in the Posthumanities-series edited by Cary Wolfe.

Insect Media

An Archaeology of Animals and Technology

Jussi Parikka

Uncovering the insect logic that informs contemporary media technologies and the network society

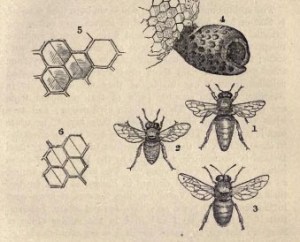

Since the early nineteenth-century, when entomologists first popularized the unique biological and behavioral characteristics of insects, technological innovators and theorists have proposed the use of insects as templates for a wide range of technologies. In Insect Media, Jussi Parikka analyzes how insect forms of social organization—swarms, hives, webs, and distr ibuted intelligence—have been used to structure modern media technologies and the network society, providing a radical new perspective on the interconnection of biology and technology.

ibuted intelligence—have been used to structure modern media technologies and the network society, providing a radical new perspective on the interconnection of biology and technology.

Through close engagement with the pioneering work of insect ethologists, including Jakob von Uexküll and Karl von Frisch, posthumanist philosophers, media theorists, and contemporary filmmakers and artists, Parikka develops an “insect theory of media,” one that conceptualizes modern media as more than the products of individual human actors, social interests, or technological determinants. They are, rather, profoundly nonhuman phenomena that both draw on and mimic the alien life-worlds of insects.

Deftly moving from the life sciences to digital technology, from popular culture to avant-garde art and architecture, and from philosophy to cybernetics and game theory, Parikka provides innovative conceptual tools for understanding the phenomena of network society and culture. Challenging anthropocentric approaches to contemporary science and culture, Insect Media reveals the possibilities that insects and other nonhuman animals offer for rethinking media, the conflation of biology and technology, and our understanding of, and interaction with, contemporary digital culture.

“Jussi Parikka challenges our traditional views of the natural and the artificial. Parikka not only understands insects through the lens of of media and mediation, he also unearths an insect logic at the heart of our contemporary fascination with networks, swarming, and intelligent agents. Insect Media is a book that is sure to create a buzz.” – Eugene Thacker, author of After Life

Jussi Parikka is Reader in Media Theory and History at Anglia Ruskin University and the Director of CoDE: the Cultures of the Digital Economy research institute. He is the author of Digital Contagions: A Media Archaeology of Computer Viruses.

Theory/Media

(image from: James Rennie’s Insect Architecture, 1869)