The Media That Therefore We Are – on Lenore Malen’s video installation

I wrote this short catalogue text for Lenore Malen’s I am the Animal — also included stills (courtesy of and permission from Lenore Malen) from the exhibition:

The Media That Therefore We Are

It’s a matter of scales. If you are far enough away, and your perspective is mediated by a layer of concepts, abstractions, and an organizational eye, you might indeed see them as models of ideal society. It’s all order. Everyone does what they are supposed to. There is one Queen. No wonder the protofascist Maya the Bee was an ideal cartoon character for 1930s national-socialist Germany. One is tempted to see the idea of a strong leadership to which everyone submits as an example of sovereign power per se, even if, to be honest, the Queen does not choose to execute power — it happens much more intuitively, almost in a subconscious way. Of course, when it comes to bees, there is no such talk of subconscious; instinct used to be the word in the 19th century for this near mystical mode of organization. This is evident in, for instance, Maurice Maeterlinck’s The Life of the Bee (1901), which refers to “the spirit of the hive.”

But on another scale, it looks very different. Look closely enough and they become the aliens they are: their weird compound eyes composed of thousands of lenses, their six legs, non-human movement, jerky, non-mammal insides folded out. This has been the other story since the 19th century and the birth of modern entomology: insects as aliens, otherworldly non-humans, often seem almost to possess technology in their capacities to see, sense, and move differently. The insects are the Anti-McLuhan; technics does not start with the human but with the animal, the insect, and their superior powers of being-in the- world (the allusion to Heidegger is intentional).

Lenore Malen’s I Am The Animal intertwines the various histories, aesthetics, and idealizations of the bee community as well as the bee’s relations withbeekeepers. It’s all about relations, and establishing relations with our constitutive environments — including bees. Donna Haraway talks about companion species (specifically dogs, but other animals too) as formative of our being in the world; she discusses the ways in which those relations are formative of our becomings.

Lenore Malen’s I Am The Animal intertwines the various histories, aesthetics, and idealizations of the bee community as well as the bee’s relations withbeekeepers. It’s all about relations, and establishing relations with our constitutive environments — including bees. Donna Haraway talks about companion species (specifically dogs, but other animals too) as formative of our being in the world; she discusses the ways in which those relations are formative of our becomings.

Our relation to insects is reflected in much more than the narrative aspect of Malen’s work. The immersive environment of the installation envelops the spectator in a milieu of becoming. The clips Malen uses are mini-thoughts, mini-brains, which are brought together with her digital software tools; the clips are memes that Malen excavates from online archives and audiovisual repositories, and composes into a three-channel envelope.

I Am The Animal poses the question: Can insects be our companion species? This is paradoxical in light of Derrida’s The Animal That Therefore I Am, to which Malen’s title refers. Derrida starts with the gaze of the animal — his cat, to be exact, lazily gazing at Derrida’s naked body. But catching the insect’s compound eyes is more difficult, if not impossible. For Malen, Derrida’s essay functions as a critique of subjectivity. Derrida continues to analyze how the cat does not feel its own nakedness, has no need of clothes, whereas we — as technical beings — surround our bodies, envelop ourselves in extensions, such as clothes. We are not only enveloped in cinema, media, and technology but in fundamental forms of shelter.

So do animals have technology? They might not plan buildings and produce external tools, but an alternative lineage claims that animals, insects and such, are completely technical. Henri Bergson was of such an opinion: even if humans are intelligent in the sense of being able to abstract, plan, and externalize their thoughts into tools, insects occupy technics in their bodies and embody intertwining with the world. The body itself is already technical. One could think of examples of insect architecture, of various stratagems of the body for defense or attack, of modes of movement, and of perception as media. If the body is media — as Ernst Kapp suggested in the 19th century and McLuhan later — then what kind of media does the insect suggest?

The three screens of I Am The Animal are rhythmic elements that deterritorialize our vision. A slowly progressing multiplication of viewpoints is the becoming-animal of perception that the installation delivers. The immersive space is also one of measured fragmentation into the compound vision of insects. Slow disorientation is one tactic of this mode of becoming; it points both to the world of insects and to the media in which we are immersed. The early avant-garde connection between the technical vision machine and the insect compound machine — in the words of Jean Epstein, “the thousand-faceted eyes of the insects” — creates a sense of space as split; perspective is multiplied into a variation. Malen’s I Am The Animal is about such forms of multiplicity.

The animal is incorporated into the machinated cultural assemblages of modernity; the disappearance of animals from urban cultures during the past couple hundred years is paralleled by the appearance of animals in various modern discourses from media to theory. We talk, see, incorporate animal energies. Akira Mizuta Lippit in Electric Animal (2000) writes how “the idioms and histories of numerous technological innovations from the steam engine to quantum mechanics bear the traces of an incorporated animality. James Watt and later Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, Walt Disney, and Erwin Schrödinger, among other key figures in the industrial and aesthetic shifts of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, found uses for animal spirits in developing their respective machines, creating in the process fantastic hybrids.”

Animals as well as media are elements with which we become. Matthew Fuller in his essay “Art for Animals” (2008) identifies a two-fold danger in relation to art with/about nature: that we succumb to a social constructionism or that we embrace biological positivism. And yet, we need to be able to carve out the art/aesthetic in and through nature and animals in ways that involve the double movement back and forth between animality and humanity. Art for animals is one way, to quote Fuller: “Art for animals intends to address the ecology of capacities for perceptions, sensation, thought and reflexivity of animals.” What kind of perceptions and sensations are afforded us by media/ nature? And conversely, what worlds do we create in which animals and nature perceive, live, and think?

Announcing Medianatures and Living Books About Life

It’s (a)live! Medianatures: The Materiality of Information Technology and Electronic Waste and the whole impressive series of 21 open access books about humanities-science-themes, commissioned by Gary Hall, Joanna Zylinska and Clare Birchall, published by Open Humanities Press and funded by JISC: Living Books About Life.

It’s (a)live! Medianatures: The Materiality of Information Technology and Electronic Waste and the whole impressive series of 21 open access books about humanities-science-themes, commissioned by Gary Hall, Joanna Zylinska and Clare Birchall, published by Open Humanities Press and funded by JISC: Living Books About Life.

My edited book was inspired by Sean Cubitt’s (and others, see the Acknowledgements of the introduction) recent research into media and waste, and I owe full thanks to him. What I wanted to investigate was the question of how materiality can be thought through such “bad matter” of waste, and related to for instance energy (consumption). The introduction outlines my approach, and ties it together with some debates in new materialism (this side of the argument is more fully outlined in a short text of mine “New Materialism as Media Theory”, forthcoming very soon in Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies-journal).

The best introduction to the whole project is however found in this press release by Hall, Zylinska and Birchall:

____________

Open Humanities Press publishes twenty-one open access Living Books About Life

LIVING BOOKS ABOUT LIFE

http://www.livingbooksaboutlife.org

The pioneering open access humanities publishing initiative, Open Humanities Press (OHP) (http://openhumanitiespress.org), is pleased to announce the release of 21 open access books in its series Living Books About Life (http://www.livingbooksaboutlife.org).

Funded by the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC), and edited by Gary Hall, Joanna Zylinska and Clare Birchall, Living Books About Life is a series of curated, open access books about life — with life understood both philosophically and biologically — which provide a bridge between the humanities and the sciences. Produced by a globally-distributed network of writers and editors, the books in the series repackage existing open access science research by clustering it around selected topics whose unifying theme is life: e.g., air, agriculture, bioethics, cosmetic surgery, electronic waste, energy, neurology and pharmacology.

Peter Suber, Open Access Project Director, Public Knowledge, said: ‘This book series would not be possible without open access. On the author side, it takes splendid advantage of the freedom to reuse and repurpose open-access research articles. On the other side, it passes on that freedom to readers. In between, the editors made intelligent selections and wrote original introductions, enhancing each article by placing it in the new context of an ambitious, integrated understanding of life, drawing equally from the sciences and humanities’.

By creating twenty one ‘living books about life’ in just seven months, the series represents an exciting new model for publishing, in a sustainable, low-cost, low-tech manner, many more such books in the future. These books can be freely shared with other academic and non-academic institutions and individuals.

Nicholas Mirzoeff, Professor of Media, Culture and Communication at New York University, commented: ‘This remarkable series transforms the humble Reader into a living form, while breaking down the conceptual barrier between the humanities and the sciences in a time when scholars and activists of all kinds have taken the understanding of life to be central. Brilliant in its simplicity and concept, this series is a leap towards an exciting new future’.

One of the most important aspects of the Living Books About Life series is the impact it has had on the attitudes of the researchers taking part, changing their views on open access and raising awareness of issues around publishers’ licensing and copyright agreements. Many have become open access advocates themselves, keen to disseminate this model among their own scholarly and student communities. As Professor Erica Fudge of the University of Strathclyde and co-editor of the living book on Veterinary Science, put it, ‘I am now evangelical about making work publicly available, and am really encouraging colleagues to put things out there’.

These ‘books about life’ are themselves ‘living’, in the sense they are open to ongoing collaborative processes of writing, editing, updating, remixing and commenting by readers. As well as repackaging open access science research — together with interactive maps and audio-visual material — into a series of books, Living Books About Life is thus involved in rethinking ‘the book’ itself as a living, collaborative endeavour in the age of open science, open education, open data, iPad apps and e-book readers such as Kindle.

Tara McPherson, editor of VECTORS, Journal of Culture and Technology in a Dynamic Vernacular, said: ‘It is no hyperbole to say that this series will help us reimagine everything we think we know about academic publishing. It points to a future that is interdisciplinary, open access, and expansive.’

Funded by JISC, Living Books About Life is a collaboration between Open Humanities Press and three academic institutions, Coventry University, Goldsmiths, University of London, and the University of Kent.

Books:

* Astrobiology and the Search for Life on Mars, edited by Sarah Kember (Goldsmiths, University of London)

* Bioethics™: Life, Politics, Economics, edited by Joanna Zylinska (Goldsmiths, University of London)

* Biosemiotics: Nature, Culture, Science, Semiosis, edited by Wendy Wheeler (London Metropolitan University)

* Cognition and Decision in Non-Human Biological Organisms, edited by Steven Shaviro (Wayne State University)

* Cosmetic Surgery: Medicine, Culture, Beauty, edited by Bernadette Wegenstein (Johns Hopkins University)

* Creative Evolution: Natural Selection and the Urge to Remix, edited by Mark Amerika (University of Colorado at Boulder)

* Digitize Me, Visualize Me, Search Me: Open Science and its Discontents, edited by Gary Hall (Coventry University)

* Energy Connections: Living Forces in Creative Inter/Intra-Action, edited by Manuela Rossini (td-net for Transdisciplinary Research, Switzerland)

* Human Genomics: From Hypothetical Genes to Biodigital Materialisations, edited by Kate O’Riordan (Sussex University)

* Medianatures: The Materiality of Information Technology and Electronic Waste, edited by Jussi Parikka (Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton)

* Nerves of Perception: Motor and Sensory Experience in Neuroscience, edited by Anna Munster (University of New South Wales)

* Neurofutures, edited by Timothy Lenoir (Duke University)

* Partial Life, edited by Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr (SymbioticA, University of Western Australia)

* Pharmacology, edited by Dave Boothroyd (University of Kent)

* Symbiosis, edited by Janneke Adema and Pete Woodbridge (Coventry University)

* Another Technoscience is Possible: Agricultural Lessons for the Posthumanities, edited by Gabriela Mendez Cota (Goldsmiths, University of London)

* The In/visible, edited by Clare Birchall (University of Kent)

* The Life of Air: Dwelling, Communicating, Manipulating, edited by Monika Bakke (University of Poznan)

* The Mediations of Consciousness, edited by Alberto López Cuenca (Universidad de las Américas, Puebla)

* Ubiquitous Surveillance, edited by David Parry (University of Texas at Dallas)

* Veterinary Science: Animals, Humans and Health, edited by Erica Fudge (Strathclyde University) and Clare Palmer (Texas A&M University)

W: http://www.livingbooksaboutlife.org

Open Humanities Press is a non-profit, international Open Access publishing collective specializing in critical and cultural theory. OHP was formed by academics to overcome the current crisis in scholarly publishing that threatens intellectual freedom and academic rigor worldwide. OHP journals are academically certified by OHP’s independent board of international scholars. All OHP publications are peer-reviewed, published under open access licenses, and freely and immediately available online at http://openhumanitiespress.org

Speed — neoliberalism

A poster I spotted on the dangers of speed — although, Ali G might have asked after reading half-way through: “but where are the downsides?”.

A poster I spotted on the dangers of speed — although, Ali G might have asked after reading half-way through: “but where are the downsides?”.

And after reading the rest, you start thinking: is this not…everyday life in neoliberalist capital culture, where you feel like that anyway after a normal work day?

After these thoughts, read this “The Political Economy of Unhappiness” (New Left Review).

A quote from the article: “One contradiction of neo-liberalism is that it demands levels of enthusiasm, energy and hope whose conditions it destroys through insecurity, powerlessness and the valorization of unattainable ego ideals via advertising.”

Winchester Speaker Series: Phillips and Milne

We are today kicking off our new research centre seminar series with John Phillips (National University of Singapore) and his talk “Seeing Things” – which promises to address Bernard Stiegler, military technologies and critical theory.

And next week Thursday, continuing with Esther Milne with Siegert, not Stiegler!

THE WINCHESTER CENTRE FOR GLOBAL FUTURES IN ART, DESIGN & MEDIA

Seminar Series: 3 November 2011, 5 pm at seminar room 8-9.

‘Technologies of Presence: Intimate Absence and Public Privacy’

Esther Milne

Intimacy, affect and image are always intertwined at the level of technology. The practices of mail-art, for example, are enabled by the material conditions of the postal exchange. In turn, the economies of this exchange are underpinned by the dance between absence and presence: writing a letter signals the absence of the recipient and, simultaneously, aims to bridge the gap between writer and recipient.

This paper traces the production of presence across nineteenth century postal networks in order to make some preliminary remarks about twenty first century platforms of social media, such as Twitter. In particular it explores the emergence of contemporary patterns of ‘public privacy’ through their socio-technical historical settings. Postcard media offers one such site. As Bernhard Siegert and Jacques Derrida have demonstrated, the postcard operates as a liminal figure for the reformulation of public and private communication.

‘Public Privacy’ describes the ways in which subjects use the public signifying systems of social media to produce images of love, desire and pain. Yet such rhetorical strategies are not unique to distributed digital platforms. After all, the eighteenth century epistolary network, often called ‘The Republic of Letters’, was responsible for reconfiguring the public and private domain. Through an exploration of mail-art practice, this paper identifies the postal principle of Twitter to challenge recent claims for the ‘death of privacy’.

BIO: Dr Esther Milne is Deputy Head of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences at Swinburne University, Melbourne, Australia. She researches in the areas of celebrity production within legislative and cultural contexts; and the history of networked postal communication systems. Her recent book, Letters, Postcards, Email: Technologies of Presence, is published by Routledge.

Friedrich Kittler (1943-2011)

Writing anything after hearing about the death of Friedrich Kittler (1943-2011) is not really easy, even if it surely will boost the academic publishing industry into a range of publications. Somewhere I read him characterized as the “Derrida of media theory” and where the writer (probably Winthrop-Young or Peters) added that of course, Kittler would like to be called “Foucault of media theory”. But then again,

Winthrop-Young or Peters) added that of course, Kittler would like to be called “Foucault of media theory”. But then again,

I think he would have liked to be thought of as, well, I guess “Any-Band-Member-of-Pink-Floyd – of Media Theory”.

Quite emblematically, as happened with the translation and cultural import of French theory to English speaking academia, things got mixed. German media theory became a general term that mostly hide a lot of differences between writers. Same thing had happened with French Theory when it arrived in the US. In media theory, Kittler became however the leading figure, due to the two translations: in 1990, Aufschreibesystem got its English form as Discourse Networks, and in 1999 Gramophone Film Typewriter came out. Meanwhile, his essays started to pour into English language. On computers, literature, psychoanalysis, music and sound, and optical media – the classes he gave in 1999, translated into English later as Optical Media (2010). He wrote a lot, and his amazing expertise from literature to physics and engineering produced something eclectic – a weird world of Pynchon and voltages, of Goethe and dead voices of phonographic recordings, a mix of sex, Rock’n’Roll and philosophy. Pink Floyd was as important to him as Foucault (see the wonderful little book by Winthrop-Young), and he never really believed in Cultural Studies.

We had the honour of hosting his last talk at Sophienstrasse, and probably his last public talk ever. The Medientheater was jam packed, primarily because of Kittler, talking at the last event of the Sophienstrasse 22 address. Even then he continued along the same line of thought: critique of the standardization of university worlds. He was an adamant defender of the old(er) ideas of university, before the subsuming of the education system to short-term market terms, the creative industries, the psychobabble that is unscientific and leads to a deterioration of intellectual goals. Despite being a fan of “Old Europe”, he was against the BA-MA structure reforms (the Bologna process) that offered standards for degrees across Europe. Similarly as he was offering meticulous analysis of the work of standards in computing, he did so in terms of education system, which, as we know, is just another program. It programs us, into suitable subjects – from Goethe-zeit, to the neoliberal programming of little entrepreneurs.

For such universities, Heidegger, Deleuze, Whitehead, Kittler might be seen at times too difficult, which means that we should push them more. The legacy of Kittler has been debated already during his lifetime, with Winthrop-Young in Kittler and the Media nicely remarking: “Is there a ‘Kittler School’? Yes, but it is not worth talking about. As in the case of Heidegger, clones can be dismissed, for those who choose to think and write like Kittler are condemned to forever repeat him.” Instead, continues Winthrop-Young, we need to be aware of the Kittler-effect and the impact he had to so many discussions. For me, personally, this happened through the combination of Kittler and Deleuze; reading groups in the late 1990s in Turku (largely because of a couple of people at the University: professor Jukka Sihvonen, and my friend, colleague Pasi Väliaho, along with our Deleuze-reading group together with Teemu Taira). That provided another road already, one that Kittler never really took, and which lead to thinking technics and Deleuze-Guattarian philosophy in parallel lines. Kittler might have hated that, but that is the point; keeping his legacy alive means new ideas and combinations. What I would like to sustain from his fresh, radical, anarchist ideas are the eclectic method of crisscrossing ontological regimes across science and arts; his keen historical (some would say “archaeological”) focus even if not always correct in details; his materiality, and no-nonsense attitude to theories and analysis of for instance digital media. That is much more than most of the current writing can still offer. Of course, there is so much that I refuse to take aboard, but that should be part of any intellectual reading and adaptation.

People often remember his older writings – and the idea of discourse networks, then developed into media theory. Yet, the past years he was occupied with the Greeks and what remained mostly an unfinished project: Music and Mathematics. He never reached the final book of the series on Turing-zeit, unless somewhere in his study there is a manuscript waiting to be found. Fragments for sure.

The amount of inspiring ideas he was able to pack even to a one sentence – where you were not always sure what it even meant, but you got the affective power of it. One of my favourites was the quote from Pynchon with which he started his Gramophone Film Typewriter: “Tap my head and mike my brain, Stick that needle in my vein”.

In a way, Kittler wrote media theory with Heidegger, but also with Pynchon. Gravity’s Rainbow is one key to his early writings, when you realize the style, but also the ontology behind it. Subjectivities wired to technologies, and high physics being the language “behind” the everyday appearance and seeming randomness that is just an effect of the complexity of science and engineering. The V-2 is one reference point for modern technology in general. It has a special relation to human sensorium:

“As the pendulum was pushed off center by the acceleration of launch, current would flow—the more acceleration, the more flow. So the Rocket, on its own side of the flight, sensed acceleration first. Men, tracking it, sensed position or distance first. To get to distance from acceleration, the Rocket had to integrate twice—needed a moving coil, transformers, electrolytic cell, bridge of diodes, one tetrode (an extra grid to screen away capacitive coupling inside the tube), an elaborate dance of design precautions to get to what human eyes saw first of all—the distance along the flight path.”

In short, what Guattari summed up in short that “machines talk to machines before talking to humans”, for Kittler is an elaborate work of physics and engineering, even before we see what hit us. And hear it afterwards.

Pynchon, and Gravity’s Rainbow, tie of course to Kittler’s other passion where the rocket technology took us after the war. The moon, Pink Floyd‘s moon to be specific. One is almost expecting to hear Kittler’s rusty voice whispering at the end, after the crackling LP almost finishes…”There is no dark side of the moon really…as a matter of fact, it’s all dark.”

It’s All in the Technique

Heads up on what looks like a great little Dossier of German Media Philosophy – in the new issue of Radical Philosophy (169). Indeed, as Eric Alliez in his short (hence telegraphic?) afterwords points out, this is not philosophy of media, as we might tend to think, for instance in the English language academia. It is not so much of philosophy about the media, but how philosophy and media share a certain a priori.

I myself co-edited a collection of Continental Media Philosophy in Finnish in 2008, following this idea of (positive) separatism of a certain German agenda concerning philosophy in the age of media. And it’s not only the slightly worn idea that we need to rethink philosophy because we have the internet, but understanding how the a priori of humanities might actually be technical media. This is not a techno-determinist statement in the a-historical sense, but something that at least tries to account for the birth of modern humanities in the 19th century at the same time technical media was giving us a new ontology (and hence epistemology) of the world.

What is disturbing about this special issue is the generic problem of German academia and often media theory: it’s lack of women. Whereas one could say that the dossier and the conference at Kingston University that preceded it just honestly replicates the situation, it merely replicates the bias. Lack of such people like Sybille Krämer, Marie-Louise Angerer or Eva Horn – or any younger scholars! – is unfortunate, and it seems that this blind spot was transported along with the conference, the translations to Radical Philosophy now.

This of course does not take strength away from some of the texts. Without offering a full-fledged review of the issue, I just want to point out the joy it brings me to read Bernhard Siegert. This time his short text “ The Map Is The Territory” is about something, well, not obvious to media studies: maps. But what the article turns out to be is both an investigation into the epistemological cultural practice, or technique, of map-making, the question of representation and explication what Cultural Techniques are for the German media theorists. As pointed out in a recent e-mail to me, Geoff Winthrop-Young (who is the true expert in these matters) too underlines how important of a concept it is, and represents something that the Anglo-American reception of “German media theory” has still not started to grasp. As such, for the English speaking audience, Siegert’s text is the best entry point to the concept that does not reduce itself to Marcel Mauss’ bodily techniques, nor even completely to Michel Foucault’s ideas of practices (where it however takes a lot of its inspiration).

As Siegert emphasizes, the concept is post-media but not as leaving media behind, but post as in “post-new-media” and wanting to take distance from Internet studies or mass media studies (not a surprise if you are a scholar in the Kittlerian vein). It seems like a mixed bag, the way he outlines it, inclusive of techniques of measurement and time, like calendars, to techniques of hallucination and trance. And yet, as a mixed bag, it resonates closely with what emerged since the 1980s as “German media studies” – often referred to as media archaeology too:

“The concept of cultural techniques thereby took up a feature that had been specific to German media theory since the 1980s. This specific feature set apart German media studies from Anglo-American media studies, as well as from French and German studies of communications let alone sociology, which, under the spell of enlightenment, in principle wanted to consider media only with respect to the public. German media analysis placed at the basis of changes in cultural and intellectual history inconspicuous techniques of knowledge like card indexes, media of pedagogy like the slate, discourse operators like quotation marks, uses of the phonograph in phonetics, or techniques of forming the individual like practices of teaching to read and write. Thus media, symbolic operators and practices were selected out, which are today systematically related to each other by the concept of cultural techniques.” (14)

I think that long quotation was worth it to illuminate the centrality of the concept, which has enjoyed a bit of visibility in the name of such institutions as the Berlin Helmholtz Centre for Cultural Techniques.

In another context, Siegert has called this media archaeological 1980s as a phase of gay science– of exploration and fresh ideas. Indeed, I have to agree on some of his critique that he points towards some of the dogmatic media and cultural studies that already from the beginning know the research results: The Marxists always find the commodity form, and Cultural studies always finds race, gender and class. Interestingly, whereas a lot of Cultural and Media Studies for instance in the Anglo-American world brought with it a suspicion of ontology as something that still smells like the old library books of metaphysics, and a focus on epistemology (preferably linguistically determined, representational, or at least empirical), the emphasis on knowledge and epistemology that one finds in cultural techniques is slightly different. Epistemology is indeed embedded in a range of practices from the body to science (obviously), but at the same time Siegert insists that part of the work of analysis of cultural techniques is to investigate how cultural practices are everywhere – to take his example, for instance no time outside techniques of time. And yet, Siegert does not turn his back on ontology. Let’s quote again: “ This does not imply, however, that writing the history of cultural techniques is meant to be an anti-ontological project. On the contrary, it implies more than it includes a historical ontology, which however does not base that which exists in ideas, adequate reason or an eidos, as was common in the tradition of metaphysics, but in media operations, which work as conditions of possibility for artefacts, knowledge, the production of political or aesthetic or religious actants.” (15) There is no mention of Ian Hacking in this context by Siegert, but for someone with a bit time on their hands, there are possibilities to track some connections to recent years of “new materialism” too.

When Siegert picks up on Gilbert Simondon, the critique of hylomorphism and embracing the idea of cultural techniques (and as I too have called media archaeology) as Deleuze-Guattarian nomadic science, we are on to the specific emphasis on materiality again. This however is not a materiality determined by a clean-cut causality chains from scientific-engineering solutions, but one that investigates them in a bundle with techniques of various ranges. Across a historical hylomorphic assumption of separation of content and form, things interfere across such regimes – like in maps, materiality infects the content. And as such, the interference offered by some such texts might be a really excellent distraction if you are bored reading the introductions to mass media or introductions to representations of media content, that still fills our media studies understanding.

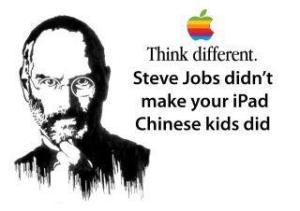

Jobs, we need jobs

Just a sober reminder of some of the work that enabled Jobs to be the (media) star he was. This via Facebook.

Rhythm & Event: The Aesthetico-Technical

The London Graduate School, Kingston University, presents a one day symposium on Rhythm & Event, Saturday 29 October 2011, King’s Anatomy Theatre and Museum.

Can a concept of rhythm, understood as a vibrational, irregular, abstract-yet-real movement, lurking at the unknown dimensions of the event, bridge the gap between actual & virtual, analog & digital, spatial & temporal, as well as between theories & practices of sound? The purpose of this symposium is to elaborate a philosophy of rhythm as an appropriate mode of analysis of the event, and a method with which to account for the process of change and the production of novelty in contemporary environments.

Plenary speakers include, Matthew Fuller (Goldsmiths College) & Andrew Goffey (Middlesex University), Angus Carlyle (LCC, CRiSAP), and Jussi Parikka (Winchester School of Art/ University of Southampton). The event will conclude with an electronic audiovisual performance and wine reception.

For details and registration, please visit this link: tiny.cc/rhythm-lgs

And my talk at the event, at least an approximation of this summary:

The Aesthetico-Technical Rhythm

Despite the insistence on the objective materiality as a grounding for technical media culture, a key realization that framed also technical media was that of rhythm – or more widely vibrations, waves, rhythms, and patterns. From the 19th century discoveries concerning Hertzian waves and Fourier transformations, Helmholtz and Nikola Tesla to mid 20th century research into brains and brain waves mapped and modulated through EEG (W.Grey Walter and the British Cybernetics), and onto contemporary digital culture of algo-rhythms (Miyazaki 2011), this talk maps a short genealogy of rhythmic technical media. The talk focuses especially on the epistemological mapping of sound words by the Institute for Algorhythmics (Berlin), and argues for an aesthetic-technical connection to think through the sonification of non-sensuous digital worlds. Referring to Wendy Chun’s (2011) ideas concerning the invisibility-visibility pairing in digital culture, the talk addresses not code, but rhythm as the constituting element for technical media.

Operative Media Archaeology

If interested in Friedrich Kittler, German media theory, and new approaches to archives, technical media and media archaeology – check out Wolfgang Ernst’s work. My article on his media archaeology is out now, in Theory, Culture & Society.

Having said that, Ernst is someone who is not – despite some misunderstandings in especially Anglo-American reception – a student of Kittler’s, and to make things even more complex, Kittler himself denounced being a media archaeologist. Despite such figures even in Germany as Bernhard Siegert referring to the 1980s and 1990s vibrant German media theory discussions as an age of media archaeology & Nietzschean Gay Science, Kittler himself recently took a bit distance from this particular term (even if, underlining how symphathetic he is to Ernst’s approach).

In any case, you can find the article here. I hope it to work as an introduction to Ernst’s work which is still not very well known in Anglo-American discussions. And more to come: next year or so, University of Minnesota Press is putting out a collection of Ernst writings (edited by me), which gives a deeper insight of why he might just be relevant not only as a “post-Kittler” theorist to spike up our theory discussions from that Berlin directions but also as someone who could bring an additional angle to thinking about archives and digital humanities.